A deep dive into 'Face/Off': the best, most absurd action film ever made

"Nicolas Cage kept repeating 'face... off' so many times we were worried Paramount would change the name of the film.”

You may have had some weird ideas. You may have entertained some strange notions. But for sheer balls-out absurdity, can even your most gleeful fantasy compete with the following?

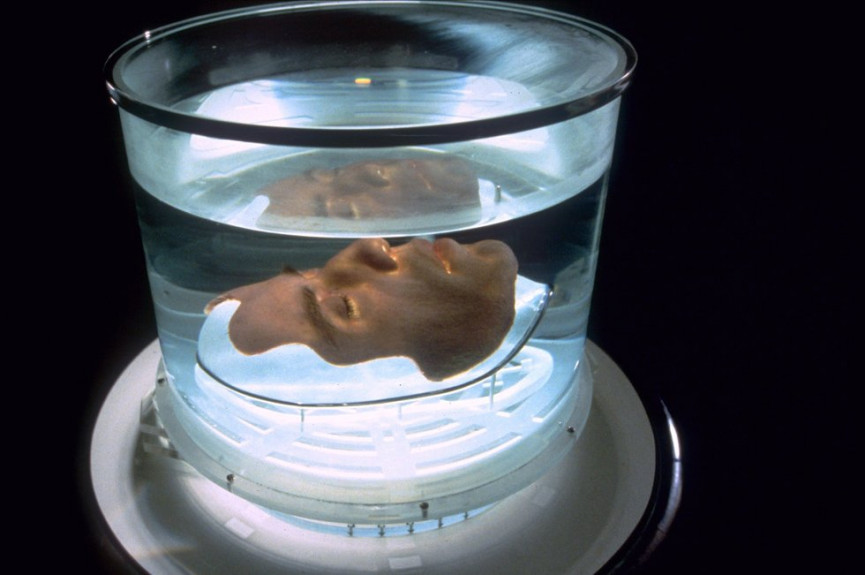

Obsessed with bringing terrorist Castor Troy (Nicolas Cage) to justice, FBI agent Sean Archer (John Travolta) tracks down Troy, who has boarded a plane in Los Angeles. After the plane crashes and Troy is severely injured, possibly dead, Archer undergoes surgery to remove his face and replace it with Troy’s. As Archer tries to use his disguise to elicit information about a bomb from Troy’s brother, Troy awakes from a coma and forces the doctor who performed the surgery to give him Archer’s face.

UPDATE: That is the plot of the 1997 movie Face/Off and, with news that the movie is being remade, here's a deep dive into the best, most absurd action film ever made...

- These are the best 90s movies of all time.

“Every studio in Hollywood was looking for the next Die Hard,” says Michael Colleary, who, along with Mike Werb, was the brains behind the baffling script. On the Independence Day weekend of 1990, five days after the second Die Hard came out, the two Mikes sat down and stroked their chins. The early 90s was an era of million-dollar spec sales, and the pair could smell the money. Inspired by the film White Heat, starring James Cagney, they imagined a plot in which their main character could survive a prison riot – an idea that mutated and evolved as the first draft took shape. This draft bore little resemblance to the insane film we know and love. Set around 100 years in the future, it was more out there but arguably made more sense by virtue of its futuristic premise: homeless people occupied a derelict Golden Gate Bridge, cars flew through the sky, and chimpanzees carried out all manual labour.

Paramount Pictures / Allstar Images

The action needed to happen in the future, went the argument, because at the time face-swapping was impossible. “When we were pitching it in 1990 it just seemed insane,” says Colleary. When the Mikes hit upon the idea that Troy and Archer could swap lives, they had discovered the “purest version” of the story. Then, says Colleary, his partner came up with the idea that Troy and Archer would each begin to enjoy their new face, and with it their new life, more than their old. This was their lightbulb moment.

Hollywood wisdom has it that you don’t pitch a spec script between Thanksgiving and January, on account of the many distractions. The Mikes’ agent therefore advised that they wait until mid-January 1991 to send Face/Off. But, on Monday, January 16, the day the Mikes had expected the phones to ring with glowing responses to the script, George H W Bush announced Operation Desert Storm: the US began to bomb Iraqi forces in an attempt to expel them from Kuwait. All of a sudden no one cared much about a film in which two guys borrow each other’s faces for a while.

One of Joel Silver’s executives (Silver had produced Die Hard, Lethal Weapon 2 and Die Hard 2 in the three years prior) talked Warner Brothers into optioning the script for 18 months. Optioning guarantees nothing; it means only that a studio will pay (just over $100,000 in this case) to think about whether they intend to develop the script. As the Mikes met Warner Brothers staff and gauged enthusiasm for the project, a sinking feeling began to set in. “It was not a very productive, creative environment for those two years and it was very discouraging,” says Colleary. One executive said that the makeup would have to be staggeringly good if the two lead actors were to look convincingly like each other – missing the pretty crucial point that the actors were simply going to swap roles.

Paramount Pictures / Allstar Images

After these teething problems with Warner Brothers, producer David Permut paid for a new option out of his pocket and the script made its way to Paramount, where it found a champion in Sherry Lansing and the first of three directors: Rob Cohen. One of Cohen’s dubious ideas was that the film could end with lifelong nemeses Troy and Archer working together to disarm the bomb that is the threat that convinces Archer to steal Troy’s face in the first place. Colleary tells me wearily that at Paramount there was also talk of the bomb becoming sentient in some way. Cohen left the film, and his ideas, diligently typed up by the Mikes, were thrown into the bin.

Next came Demolition Man director Marco Brambilla, who wanted to make the cast much younger. As Colleary tells me, “That made no sense and we were totally against it on every level.” Around this time, Paramount were trying to turn 27-year-old Johnny Depp into a movie star. The studio said that they would only agree to including Nicolas Cage – who wanted to be in the film – if Depp could star opposite him. After finally reading the script, however, Depp refused to take part. Having read the title he thought the film would be about hockey. He was disappointed when he discovered that it was not about hockey. He was out – and with him so was Brambilla. As Colleary puts it, “A lot of things had to go wrong to help this movie along.”

At last, however, four years after the script entered the world, the stars began to align. The Mikes watched The Killer, the Hong Kong action movie by John Woo, and realised something. “Holy shit,” they said to themselves. “Face/Off is a John Woo movie.” They were in luck: unbeknownst to them, Woo had read and liked the Face/Off script. He was making Broken Arrow with John Travolta, who had found his mojo again after 1994’s Pulp Fiction. At this point, Travolta would do anything if it involved Woo. He told the Mikes that he had always wanted to star in a film about good and evil twins. Now that Travolta was in, Cage – filming Con Air at this point – began to drift back into the frame.

Allstar Pictures

John Woo wanted to bring the plot forward to 2002 and do justice to the familial and emotional strands of the film. His involvement would lend the film many of the features for which it is cherished: billowing coats; slow-motion doves; extravagantly balletic action sequences. Face/Off was Woo’s first major Hollywood movie and he was “at the height of his creativity”, says producer Terence Chang. Everyone I interview speaks of the taciturn Chinese director as though he is some kind of god.

In the early days, opinion seemed to oscillate: the film had the potential to be a huge success but it might be a catastrophic failure. Watching it now, you can see that it walks that tightrope, with one foot dangling precariously over the edge. “I put in a bid for a house in Beverly Hills that had been accepted the day we started production,” says Mike Werb, “and I backed out of buying that house because I got completely paranoid: this movie is going to be a big flop.” Rock Galotti, in charge of the weapons on the film, says, “From the moment I read Face/Off, having experienced working with John Woo, I knew that audiences would enjoy it.”

Paramount Pictures / Allstar Images

Nicolas Cage was, unfortunately, unable to talk to me for this piece because he was recovering after breaking his ankle in a freak accident in Bulgaria. I took the next logical step and sought out Marco Kyrics, his stand-in. When I meet Kyris, 150 yards away from my office, he says of the script, “I read it; I re-read it; I read it again; I said ‘This is not gonna translate onto film. This is gonna be a big flop.’” However many people were optimistic, as Colleary points out, “A lot of really smart people were not too sure.”

The reasons they were worried aren’t hard to pinpoint, as this great video forensically explores. Though Cage and Travolta were at the top of their game, the unbelievably unbelievable plot had the potential to scupper the entire project: the idea that in 2002 face-swapping technology would be so sophisticated that there would be no healing process, no scars, no imperfections; the fact that, as well as their faces swapping, the men’s bodies would be effortlessly made to look identical (ditto their voices); the fact that the men’s blood types are explicitly described as being different, meaning no transplants at all would actually be possible; the fact that Castor Troy is incarcerated in a magnetic prison; the fact that at one point Troy tells Archer he doesn’t know which he hates more, wearing Archer’s face or his body, despite the fact that he’s only wearing his face; and numerous other absurd implausibilities.

“I have no problem with people pulling it apart,” Colleary says of the film. “If you look at anything you can take it apart. So Face/Off should be no different.”

Rex Features

Before they began shooting, there was one hurdle to overcome: Travolta had notes. He invited the Mikes to his house and spent three or four hours poring over the script. Colleary was terrified the mega-star would pull the single thread that would cause the whole project to unravel. In particular Travolta wanted to discuss a line in which Troy, in Archer’s body, refers to his “ridiculous chin”. The Mikes quickly had to jump in and reassure him, says Colleary: “We said, ‘John, the joke is that you’re such a famously handsome person that saying that anyone would complain about looking like you…that’s the joke: that Nicolas Cage doesn’t understand how good-looking he now is.’” His ego massaged, Travolta seemed to believe them.

Much as I burrow to expose discord, by all accounts the filming experience seems to have been a delight. Partly because the Mikes were deemed to be the only people who understood the script well enough (or perhaps at all), they were paid to be on set constantly: “I think because people recognised they couldn’t rewrite this script without potentially really fucking it up,” says Colleary.

The two stars were markedly different. When they first met with the producers and writers, it was Travolta who was the more gregarious: he is said to be an excellent mimic, impersonating Cage and others. Werb describes Cage as being kinetic, emotional, and visceral; Travolta, by contrast, “kept a very even keel”. When it came to using guns, it was Cage who was the natural. “Nic’s extremely, extremely athletic,” says weapons man Rock Galotti. “He’s extremely focused. He’s one of the best that I’ve worked with regarding firearms. If he doesn’t own a gun, I’d definitely expect that he’s shot a gun more [than Travolta] – whether it be for work or whether it be personally.” And Travolta? “He is not into the weapons portion of it like Nic Cage is. John’s very much a family man. He’ll listen and he’ll reply to the best of his ability but sometimes he has his own character or desires on the way he wishes to do things.”

Kyris and Cage / Twitter

No one is better able to extol Nicolas Cage’s virtues than Marco Kyris, who was his stand-in on more than 20 films, following him all over the world. “He’s not a big boisterous fan-party kinda boy like John Travolta,” says Kyris of the enigmatic star. “He’s more pensive and shy. He’s the opposite of me. He comes off as very cold and arrogant but he’s always in thought. He could sit there for four hours in his actor’s chair and he would just sit there and watch and do nothing – just stare.”

Kyris followed Cage from Con Air straight onto Face/Off, with no time to catch his breath. It was the point at which Cage’s career was beginning to catch fire – he had just won his one and only Best Actor award for Leaving Las Vegas. Kyris says he is not being arrogant when he describes himself as being like a producer on the film and likens the work of a stand-in to that of a Broadway understudy – a comparison that doesn’t quite hold because Kyris, once an aspiring actor, would never have been called on to fill Cage’s shoes if Cage had diarrhoea. It is the job of a stand-in to carry out the mundane on-set tasks that would be a waste of time for the actor: while Cage sat in his trailer working on his character, Kyris would be lighting a lighter or pulling something out of a wallet, all in an effort to convincingly look like his doppelganger. (Unlike most stand-ins, Kyris does look remarkably like the man he is paid to resemble, especially when he says “I’d like to take his face...off” right in front of me.)

One Cage trait that both Kyris and Werb mention (other than his unfailing generosity: “‘Here’s a Rolex. Here’s a Dolce and Gabbana jacket. Here’s a Gucci suit for you.’ It went on forever” says Kyris) is the actor’s ad-libbing. In one infamous scene, Sean Archer (with Castor Troy’s face) tells an associate that he wants to remove Archer’s (Troy’s) face: “I’d like to take his face…off.” Not content with namechecking the film just the once, the pair then go back and forth with variations on that sentence for literally a minute. In the script the line was never repeated; Kyris claims that Cage delivered it 18 or 20 times for no real reason, changing the intonation and movement each time, to the point of hysteria. As Werb says, “It was at that point we were worried Paramount was going to change the name of the film.”

Paramount Pictures/Rex Features

Face/Off, in Kyris’ words, was “the most exhausting film on Earth” – and, with its preposterous gunfights, multiple false endings, and exaggerated performances, it’s easy to see why. The shoot lasted five to six months and Terence Chang remembers that they shot through Christmas. On Christmas Day they were still trying to negotiate a deal for Travolta, who had started the film not knowing how much money he would get. Most stressful of all, Kyris remembers, was the film’s all-but-climactic boat chase, which took four weeks to put together. After a Mexican stand-off in a church in which Troy and Archer fail to kill each other (already the third time they have held guns to each other’s heads), the pair then leap into speed boats and embark on a chase around Long Beach Harbour, ramming the boats into each other and riding them through other boats, blowing them up into extravagant flames. “When they did it there were several mishaps,” says Kyris. “Nobody lost a life but there were some accidents.”

In the 90s, it was still common practice for film studios to publish novelisations of their movies. 1997’s Face/Off was no different. It is for this reason that we come, at last, to Clark Carlton.

Carlton, the author of the Face/Off novelisation, begins by telling me that he would rather we speak by email than phone because a journalist once misquoted him and offended some of his close friends. “I was thrilled when the Mikes asked me to write the novelisation of their film,” he says. “I knew not just that I could do it but that I should do it. I understood that this project had a certain power that was rooted in the Jungian notion of the Shadow. I’m a very lawful and polite person so it was interesting for me to indulge in some dark, selfish and destructive fantasies as well as to embellish the noble actions of Face/Off’s hero.”

Given that Carlton’s novel is 299 pages long, there are bound to be elements that diverge from the screenplay. In Carlton’s version of the magnetic prison, for example, “When a prisoner committed a third violation, he was placed in a pod, drained of most of his fluids and inserted into a slot in the ceiling.” I ask him about one of the most intriguing passages in the book: “From inside his pants, Archer felt a strange, yet familiar sensation. He was sure that inside his boxer shorts, a thousand topless French women, the size of ants, were erecting the Eiffel Tower.” If that isn’t the best encapsulation of how it feels to get an erection, I don’t know what is. “I was giving into a metaphor that included a reference to ants and to a world of tiny people which is a personal obsession,” says Carlton. “Interestingly, that sentence foreshadowed my own science fiction novel, Prophets of the Ghost Ants, also released by Harper Collins through their Voyager line in 2017…”

Allstar Pictures

Colleary tells me that Carlton’s ideas – though not the erection line specifically – actually inspired them to make script changes. But one of the key differences between the novel and the movie concerns the ending: in the novel, Castor Troy’s son Adam, orphaned when Sean Archer finally harpoons Troy to death, is “adopted by a South Dakota rancher and his wife”. When this off-screen ending was shown to test audiences, says Terence Chang, they were so invested in Adam’s narrative that they were desperate to know what had happened to him. The studio, initially reluctant to see Archer adopt Troy’s son himself – because it was un-American to adopt another man’s child – were forced to admit that they were wrong: a new ending was filmed in which Adam is welcomed into the Archer family, acting as a type of replacement for Mike, the son Troy had accidentally killed in the opening seconds of the film.

When it came out on June 27, 1997, Face/Off was one of a staggering number of iconic films. “That was a nutty, nutty, nutty summer for big movies,” says Colleary. As well as Face/Off, 1997 boasted Titanic; Jurassic Park, Men in Black; LA Confidential; Austin Powers; Good Will Hunting; Batman and Robin; Jackie Brown; The Full Monty; and The Fifth Element. Even among these heavyweights, Face/Off soared, making over $245 million at the US box office. “The critics fully embraced the film to a shocking degree,” says Werb. “For many years we were the only action film on Rotten Tomatoes that had a 100% fresh rating.” Going all in, Empire said that Face/Off had a strong claim to being “the best action film ever made”.

This incredible triumph – and the surprising harmony between critical and commercial success – ensured that, for the Mikes, life would never be the same again. Prior to Face/Off Colleary was broke; now, he says, “I haven’t been broke since that movie came out. Everything I have is really based on the success of that movie.”

Paramount / Allstar Pictures

Woo’s slow-motion ‘bullet ballet’ style, unusual at the time, went on to inspire many disciples to copy his example. And the film challenged contemporary received wisdom: that, for example, action movies are no place for big emotions. “That film really turned people around,” says Chang. “It was something people had never seen before.” For Colleary, the film was an important lesson: audacity in creation is everything in Hollywood. “The reason that movie got made is because it was so crazy,” he says.

Unsurprisingly, Clark Carlton has wisdom to offer here. “We have to accept that humans are killers, predators and inherently greedy,” says the author. “In real life, a heroic FBI agent or police detective has in some way got to become the criminal he or she is pursuing: to think like him or her in order to predict that person and bring them to justice. That process has an intriguing danger to it, a scary beauty, because it forces us to look at the basic impulses we have as human animals. All of us have the potential to be criminals and heroes.”

“I have no problem with people saying it’s crazy or it’s insane or it’s stupid,” says Werb. “It’s a fable.” While it would be tempting to point out that the numerous plot holes could easily have been resolved, Werb is right: Face/Off is a film shouldering themes whose magnitude is so vast that, frankly, it seems pedantic to want to talk about continuity. Straight out of the blocks Face/Off is a soap opera of death, of grudges and revenge. It asks us what it means to live; what it means to let go; what it means to forgive. In granting us a window into what it might be like to assume the identity of our worst enemy, it tells us things we might not want to hear about ourselves. Our fears. Our obsessions. Our darkest fantasies.

And after all, as Castor Troy says at one point, “I could eat a peach for hours.”

Latest

Related Reviews and Shortlists

The 10 best war movies of the 21st century

The best movies on Netflix: this is what to watch