Why Tetris is the most important video game ever made

Dan Ackerman, author of The Tetris Effect, explains why the deceptively simple block stacker is the most significant video game ever built

Dan Ackerman, author of The Tetris Effect, explains why the deceptively simple block stacker is the most significant video game ever built

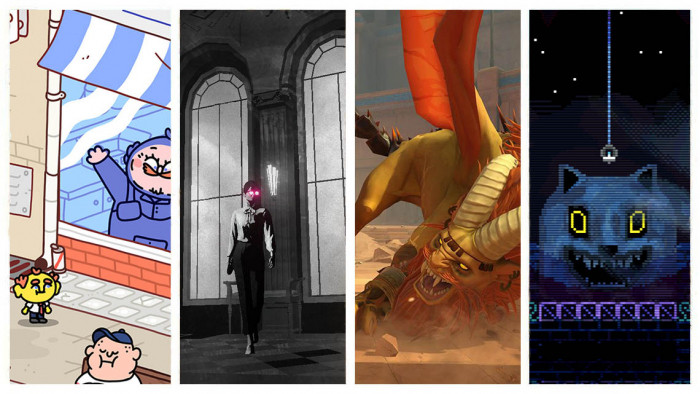

None other than Time Magazine recently tasked its expert editorial staff not with dissecting the latest from Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, but instead with ranking the 50 greatest video games of all time. Of course, for video games, "all time" only goes back to roughly 1971, but there are still so many great games to choose from, one could double or triple the size of the list and still not run out of true classics.

The number one spot on that list was taken not by Mario, Zelda, Resident Evil, Gears of War, or any of a hundred other worthwhile contenders. Not even Pac-Man - which suffered a major snub, being left off the list entirely (although Ms. Pac-Man slid into the number five slot, so I suspect it's going to be an awkward weekend at the Pac-house).

No, the number one game of all time was among the oldest and most basic, but also the most addictive and still the most relevant, Tetris. This simple puzzle game, now more than thirty years old, continues to dominate best-of lists, and even sales charts, consistently selling millions of copies whenever there's a new platform for it to jump to, like a computer virus leaping from network to network. Gaming giant Electronic Arts has sold more than 500 million copies of its version for the iPhone and other smart phones, and that's on top of the tens of millions of Game Boy, NES, and computer versions since it was initially released by UK software publisher Mirrorsoft in 1988.

Why is Tetris the game we can't stop playing?

Before Tetris and its trance-inducing waterfall of geometric puzzle pieces, video games were brain-dulling distractions for preteens, personified by Pac- Man, Super Mario Bros., and other cartoon-like kids’ fare. Tetris was different. It didn’t rely on lo-fi imitations of cartoon characters. In fact, its curious animations didn’t imitate anything at all. The game was purely abstract, geometry in real time. It wasn’t just a game, it was an uncrackable code puzzle that anyone could play, but only a few could master. Your parents played Tetris, your friends played Tetris, you’ve played Tetris, and you’ll encounter the same story in nearly every country on Earth.

Tetris has permeated popular and artistic culture. It has been included in the Applied Design collection at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, has been adapted as interactive public art installations projected onto the sides of buildings, and is the subject of an annual World Championship competition.

That's pretty impressive for a handful of lines of code written by a lone computer scientist laboring away on outdated Soviet computer equipment at the Russian Academy of Science in 1984. But the simple game Alexey Pajitnov created was one of the first viral hits of the computer era.

Of course, back then there was no commercial internet, no way to easily share content or download games. That meant, to pass a copy of Tetris along, assuming you even had access to a computer back in mid-1980s Moscow, you had to copy it to a new floppy disk (ask your parents what that was) and physically walk over to someone and hand it off, a primitive form of networking we still call sneakernet. They would make a copy and do the same thing, and within a few years, Tetris has slipped the iron curtain and landed in the UK, where big software publishers saw there was something special about this game and latched onto it.

But there are plenty of classic games to obsess over. Why do we keep coming back to Tetris year after year?

Scientists have discovered that Tetris, alone among games, has a unique effect on the human brain, making it the perfect tool for scientific research. The first and best-known way Tetris affects the brain is so pronounced, it's literally named the Tetris Effect, which is a term used in both medical and popular literature to describe the result of repetitive, pattern-based activity that eventually begins to shape the thoughts and imagination of an individual.

Tetris imprints itself as both procedural memory, which guides frequent repetition of action, and as spatial memory, which deals with our understanding of 2D and 3D shapes and how they interact. If while packing a car for a vacation you’ve seen the suitcases as tetrominoes slotting perfectly together, you’ve experienced a mild version of the Tetris Effect. If after playing Tetris, or one of its descendants, such as Bejeweled or Candy Crush Saga, you still see falling shapes or coloured blocks in the periphery of your vision, you’re one level deeper in. The most extreme examples literally rewire the brain’s ability to record information and retain memories.

This unique effect has led to a number of surprising scientific discoveries. In the early 1990s, scientists at the University of California discovered that training to become a Tetris master actually made subjects' brains more energy efficient. After long-term exposure to the game, playing harder levels required less brain energy, not more, as if Tetris itself was training the subject's mind to evolve from a gas-guzzling SUV to a modern hybrid car.

Tetris has also been used in studies at Oxford University to prevent the debilitating flashbacks of post-traumatic stress disorder, thanks to the unique neural pathways it uses, and the game shows real promise as a low-cost, easy to use field treatment, as unusual as that sounds.

More than three decades after it first crawled along the monochromatic screen of Alexey Pajitnov’s simple Electronica 60 Russian computer, Tetris lives on in tablets, laptops, smartphones, and game consoles. I have no doubt the first game many of us will download on the new iPhone 17 ten years from now will be the latest new version of the most important game in history, Tetris.

The Tetris Effect: The Cold War Battle for the World’s Most Addictive Game is out 22 September