10 most iconic moments from Marvel Comics history - chosen by Marvel writers, directors and fans

We asked the best Marvel minds in the business what their favourite Marvel comic moments are.

It’s been 80 years since Marvel Comics burst onto the scene and in the decades since the publishing house has served up some of the greatest superheroes and storylines to grace the page.

The stories have evolved over the years to reflect the political and social issues of the day and the character roster expanded to show a more diverse and progressive attitude towards what a hero can look like.

To celebrate Marvel Comics’ contribution to pop culture, Shortlist has put together some of its most iconic moments and enlisted the help of Marvel writers, directors and authors, past and present, to share their favourites too.

- Exclusive: There’s a very good reason Stan Lee wasn’t in Logan or The Wolverine

- 5 best movie endings, according to the writers of Avengers: Endgame

10 Iconic moment from Marvel Comics history

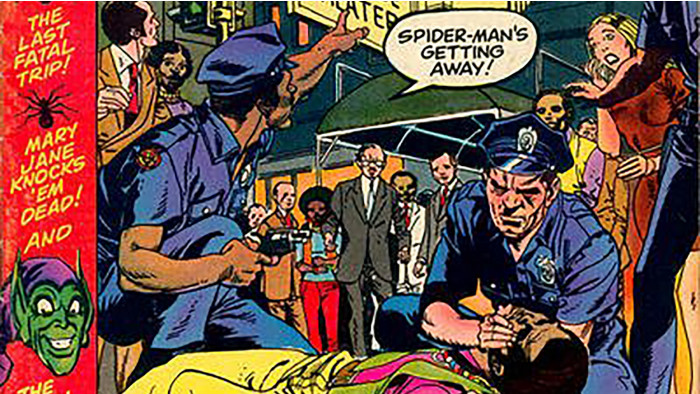

1. Stan Lee vs the Comics Code Authority

In 1971, Stan Lee had a multi-part story in the pages of Amazing Spider-Man that dealt with the dangers of drug use, and how one of Peter Parker's friends, Harry Osborn, was suffering from drug addiction. Despite the fact that it was a cautionary tale, the Comics Code Authority (set up during the ‘50s to safeguard the youth of America from anything unethical or indecent) wouldn't approve the issues because they broke one of their many hard and fast rules: the depiction of drug use.

At great risk, Stan decided to defiantly publish the comics anyway without the Comics Code Seal of Approval which, for decades, graced the cover of every comic book in America. And the world didn't end. In that one act of rebellion, Stan Lee neutered the Comics Code. It would hang around for many, many years, but it would never be the scary, Draconian thing it once was. In 1971 Stan Lee and Marvel helped change the history of comics in America... again.

Dan Slott, Marvel Comics writer (Spider-Man, Fantastic Four, Iron Man)

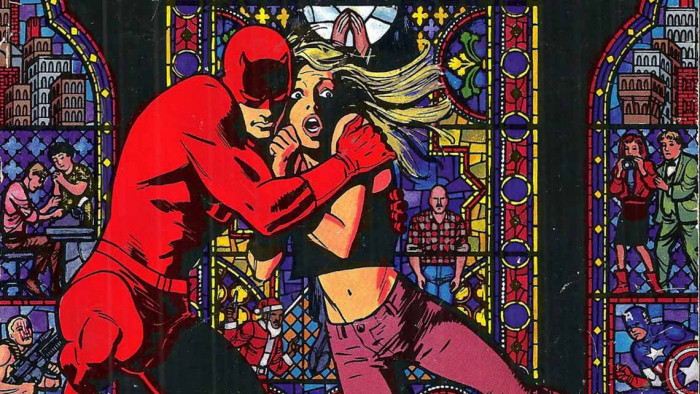

I'd have to go for Frank Miller's return to Daredevil (1986). I wasn't really reading Marvel at the time but I was reading Frank Miller. He'd left Marvel for DC after doing a multi-year run on Daredevil that reinvented a C-list character as the book everyone was talking about. Then he reinvented Batman twice, these two storylines being the basis of almost every Batman-related movie since, and then he returned to Marvel to do Daredevil: Born Again.

We were excited but hesitant. How could he top what he did before? And yet he did with an eight-issue run that beats every other Marvel comic ever published. He proved there was no such thing as a bad character if you're a good writer and this trade paperback is never far from my desk for inspiration. Thirty years on and it's still a perfect comic.

Mark Millar, comic book writer (Old Man Logan, The Ultimates, Marvel Knights Spider-Man, Ultimate Fantastic Four, Civil War)

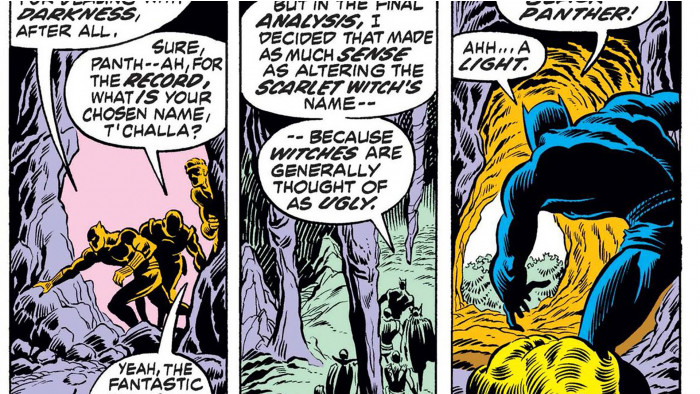

In 1966, Stan Lee and Jack Kirby introduced the first-ever black superhero to its roster with Black Panther. The Wakandan hero first appeared Fantastic Four #52 and soon enough was popping up in several other arcs including the Avengers for a few years. He then got his first leading storyline in the critically-acclaimed Jungle Action run of 1973.

What’s remarkable about this character is Lee’s refusal to portray him through negative stereotypes of African and black communities. T’Challa is a highly intelligent ruler who governs over the most technologically advanced country in the world. He’s as capable, if not more so than most of the white heroes he contends with and he has continued to be treated with that respect to become an iconic figure we can’t get enough of.

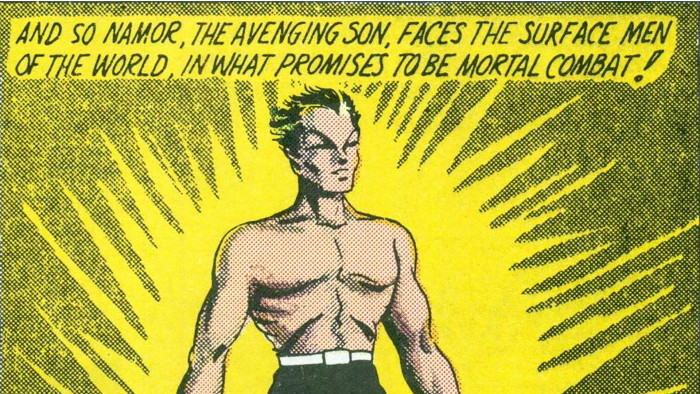

The hero-villain dichotomy was shaken up firmly with the arrival of Namor, the Sub-Mariner on the comic book scene in Marvel Comics #1, October 1939 (available to buy as part of the Folio Society’s edition of Marvel: The Golden Age). Created by writer-artist Bill Everett as the opposite and adversary of Carl Burgos’ Human Torch, Namor was the first recorded antihero.

As the mutant son of a human sea captain and a princess of an underwater race, he fought in defence of the sea against land dwellers who might harm it and for a long time was seen as the enemy of the United States. The Sub-Mariner showed there was a hunger for characters who weren’t all good or all bad, but had a specific sense of justice that let them toe the line. Namor walked so The Punisher, Black Cat, Winter Soldier and Deadpool could run.

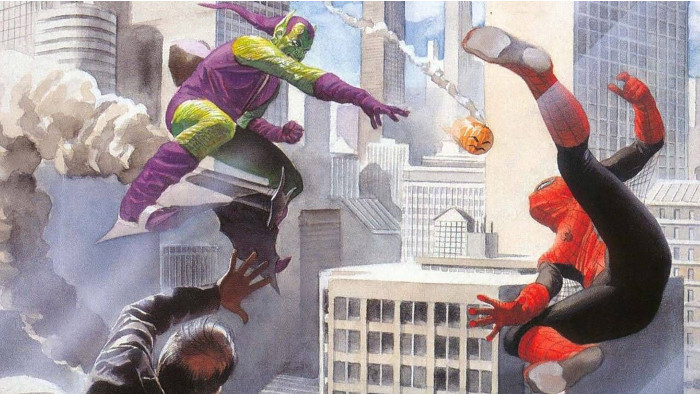

I grew up reading Marvel Comics as a kid, first Iron Man, Thor, and The Punisher then finding more niche favourites like Nomad and Slapstick. I would buy the weekly editions and read them on an episodic level, more to enjoy the artwork and the story moments than the grand overall narrative. That’s why I was particularly struck when I picked up Kurt Busiek’s 1994 limited series Marvels (which I read later in life as a trade paperback).

Busiek used an everyman perspective to examine the entire collective universe that was Marvel comic books, and I was astounded at how a singular point of view could not only consolidate the world into a unified history, but also that it could provide greater insight into heroism, tolerance, bigotry, family, and national security. Busiek looked at the entire canon and managed to weave four decades of comic book history into one storyline. That one storyline wasn’t a traditional superhero’s story, rather an average guy’s story that made the world feel much bigger and richer. In some ways, Marvels serves as a predecessor to the Marvel Cinematic Universe, of which I obviously have a great personal affection for.

Eric Pearson, screenwriter (co-wrote Thor: Ragnarok, Marvel’s Agent Carter)

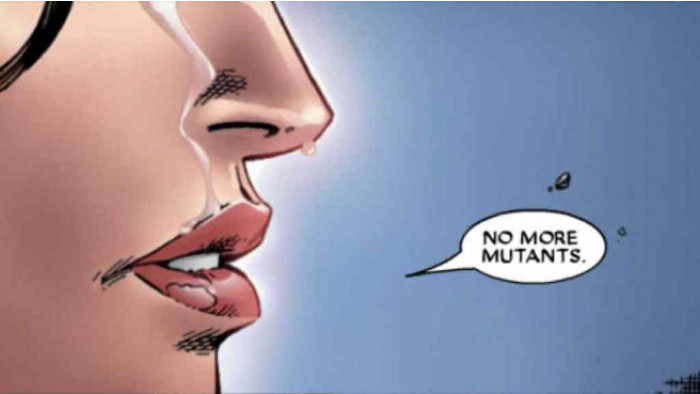

Sometimes it takes one panel to make a cataclysmic change to the fabric of Marvel Comics and that happened in 2005’s House of M #7, by Brian Michael Bendis and artist Oliver Coipel. A mentally unstable Scarlet Witch is targetted by the X-Men and Avengers after she creates an alternate reality because of the growing instability of her powers.

However, it’s because of her father Magneto’s actions that pushes Wanda over the edge to utter those three words and decimate the mutant population. From one million to just 198 mutants, this panel sent a ripple effect through the comics for the next decade, giving depowered heroes new storylines and set the groundwork for the Secret Invasion series to flourish.

It also showed just how powerful a mutant Scarlet Witch really is, which has only been touched upon in Avengers: Endgame but will likely be explored further in Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness.

In the mid-1960s, Steve Ditko introduced visual psychedelia to Marvel Comics through the character and worlds of Doctor Strange. This mind-bending imagery was progressive at the time and still holds up today as inimitable art.

In 1968, Pink Floyd borrowed Marie Severin’s Doctor Strange artwork for the cover of their psychotropic second album Saucerful of Secrets, and included the line, "and Doctor Strange is always changing size" on their 1969 follow-up album, More. This inspired me to include the song “Interstellar Overdrive” from the band's first album on the Doctor Strange movie soundtrack.

Scott Derrickson, writer and director (Doctor Strange, Doctor Strange in the Multiverse of Madness)

In February 2014, G. Willow Wilson, Sana Amanat, Adrian Alphona, and Ian Herring made history with the publication of Ms Marvel #1. Kamala Khan, taking up the mantle from her hero Carol Danvers, had arrived. And oh, what an arrival. There was that iconic cover drawn by Sara Pichelli: a clearly brown-skinned girl, hand in a fist, centring the golden lightning bolt on her t-shirt. Then there was the immediate cultural reference on the first page of her friend Nakia’s “Amreeki” nickname. Add that together with Jamie McKelvie’s instantly cosplayable costume, and we had the makings of a superstar.

But even more: there was a full first issue that dealt with issues specific to a first-generation born Pakistani and Muslim-American teenager! Wilson and Amanat gave us a character who went through things I thought I’d never see on a page: Kamala’s desperate desire to be “normal” is one that a lot of us children of immigrants deeply understand. Volume 1 of her trade is aptly named No Normal because her first story is about understanding that her identity is valid as it is. That she doesn’t need to be white, or blonde, to be strong and do good. Kamala represents a new America, one that allowed us to not only exist but to be the hero.

Preeti Chhibber, author of “Spider-Man: Far From Home: Peter and Ned's Ultimate Travel Journal”

The Marvel Cinematic Universe would arguably not be what it is today with Mark Millar and artist Bryan Hitch’s 2002-2004 reimagining of The Avengers. The Ultimates took place outside of the typical Marvel Comics’ universe and in one where the superheroes are far more flawed and more representative of the post-9/11 era. These heroes had the same names but their easy camaradie was not. They were brought together by the Samuel L. Jackson-inspired Nick Fury to work for the government-sanctioned S.H.I.E.L.D. and act more like a military squadron than a superhero team. It was both groundbreaking and uncomfortable.

The cinematic approach to the narrative and comic panels created a blueprint for the likes of Kevin Feige to work from when adapting these Marvel heroes though some of the more uncomfortable characteristics of certain characters - Hank Pym’s domestic violence, Bruce Banner’s people eating and Captain America’s Bush-era machismo - were left behind.

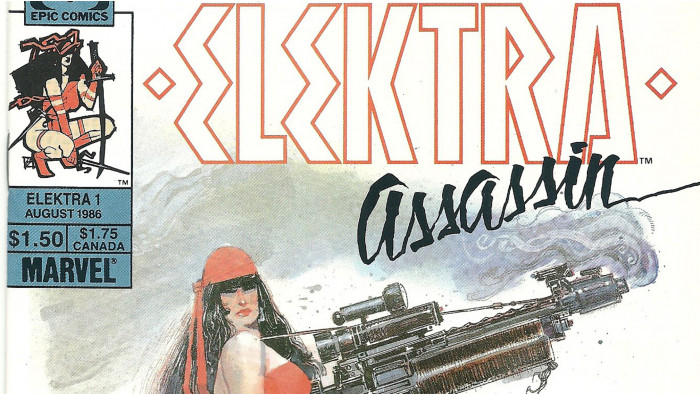

I'd love to tell you what Marvel issue I first picked up, pre-teen -- it was probably Spider-Man, or maybe the X-Men -- but the series that blew the doors off my mind came a few years later with Elektra: Assassin (1986-97). I must've been 13. I'd taken the train down to the Virgin Megastore in Brighton to buy a Jesus And Mary Chain cassette or something. But then, on the second floor, I found myself wandering through the small comics section (in fact, the signage was probably the first time I'd seen the term "graphic novels").

I was a surly Brit kid, so at this point, I was all about 2000AD because Marvel comics seemed babyish to me, a relic of childhood. But then I saw the Bill Sienkiewicz cover to the trade paperback. I honestly couldn't help but pick it up... and then WOAH. The mixed media art, the brutality, the madness - I could barely understand it, and the whole thing all felt beamed in from another planet. I felt dirty looking at it, scared even. It was visceral and trippy and emotional and creepy and so goddamn exciting that from then on, I was back into comics forever.

Drew Pearce, writer and director (Marvel One-Shot: All Hail the King, co-wrote Iron Man 3, Hotel Artemis)

Latest

Ben Affleck and Jon Bernthal talk The Accountant 2

Animal Farm movie cast announced

A Complete Unknown gets Disney Plus streaming date

Related Reviews and Shortlists