London's chicken shops - the resilient beating heart of an ever-changing city

Fried chicken is more than just fast food - it's been woven deep into the culture of the capital

It’s 10pm on a Friday night in south London. On secluded side road, nestled between old, cramped together flats and a shut down pub just a stone’s throw from the Shard, there’s a small shop noticeable by its flourescent red and white logo, and the familiar, pungent smell of warm batter and grease.

At this time of night, the shop is occupied mainly by young men in suits and loosened up ties. Presumably, they’ve just got off work in the surrounding high rise office blocks. In the corner, there’s a young family – a man, woman and their young daughter, who’ve huddled around boxes of fiery orange chicken wings, crispy fries and sparkling Fanta. Later this evening, Ali, an Iranian student who works at the chicken shop during the night, expects crowds of young people pouring in after the clubs and bars close. “We feed them, make sure they get home safe,” he laughs. “Sometimes, we are more like babysitters”.

For decades, Chicken shops have been a core part of London high streets and city centres. In some areas, it’s these shops, who in spite of their reputation, keep the streets alive. Chicken Cottage – one of Britain’s largest fast food chains – pumps in more than £50 million into the British economy each year. Other well known chains, along with the independent franchises, also light up the streets. There isn’t really a street where you wouldn’t find a Favourite Chicken, Tennesse’s, Dixy or Morley’s packed to the brim on a Friday night. In fact, Chicken shops are such a staple of the city that London mayor Sadiq Khan even suggested there were too many of them.

It’s sort of strange really. Most of these shops sell the same products, which, by and large, taste the same too. And the appeal doesn’t really translate into quality either; despite hundreds of artisanal, organic, corn-fed fried chicken joints popping up all over the city, there’s still a seemingly endless supply of cheap, soggy breaded chicken and chips all served in poorly put together cardboard boxes.

That’s because fried chicken has gone beyond just fast food – it’s been woven into the cultural fabric of the capital. Chicken shops are places that now provide familiarity in a capital rapidly being eclipsed by unaffordable apartment blocks, wine bars and exclusive members clubs. TV channels commission series centred around the people who find solace in their local joint. Chicken shops have always had a place in grime music, and catapulted into the mainstream through Stormzy’s latest video. And of course, hit YouTube series like Chicken Shop Date and The Pengest Munch have built up a cult status largely rooted in London’s love affair with stripped down chicken joints.

I like to think that everyone has their own relationship with their local chicken joint. For me, growing up in a Muslim family just outside of London, going out for fried chicken was also a rare opportunity to leave the stuffy suburbs for a glimpse of the city life, and the freedom it could offer in the form of tasty, and most importantly, Halal food. To this day, eating fried chicken still holds a sort of sentimental value, a sort of comfort meal that lets you know that in London, I’m home.

Other people I spoke to while writing this attached similar affinities to fried chicken. From first loves over chicken and chips, to first break ups over the same meal. Some people met their best friends in these shops after a night out while others remember deep, drunken conversations about their lives with the guy behind the counter.

In a changing city, though, chicken shops are more than just a scrapbook memory of coming of age . They’re also indicative of the changing nature of the capital, particularly on the impact they have on its most vulnerable citizens. And for some, like the Somali family eating at the shop this evening, the chicken shop provides a rare, affordable place to eat out occasionally. The family invited me to eat with them, but didn’t want to provide me their last name (for immigration reasons). Mohamed, the father, told me that as recent immigrants, the fried chicken shops were places they could feel comfortable, and, vitally, find food that was Halal.

“We fled from the war in Mogadishu,” he tells me, as he takes a bite into a hot, crackling chicken leg. “The first few weeks we were here, we knew where nothing was. There was no Somali community, no nothing… we ate beans, bread and cheese. That’s it.” Finding this shop, and the Arabic ‘Halal’ symbol behind the counter, was a blessing for them. “It was the first time we had eaten meat in months,” he says, as he dips chips in a small packet of ketchup. “But also, I could talk to the people who work here, who are Muslims. They can tell me where to pray, where to find work. They helped my family when there was no one else.” Mohamed currently has a job filling up crates at a local supermarket, and hopes that in a few years he will have enough money to send his daughter to University. Oxford, he hopes.

There’s no doubt that chicken shops will stand the test of time in London, and perhaps that’s because of a cult-like protection of them. Sure, for some people the shops will just be a way of getting something cheap and tasty after a big night out, but the chicken shop is more than instant gratification in the form of salt and sucrose. They’re also places that are quick to adapt to the developing capital. Places where those at the brute end of gentrification and austerity can find some sort of home and some sort of comfort blanket. And in post-Brexit Britain, when London greets anything that can be monetised with lavishness and riches, it’s in the back alley, side street chicken shops where the true spirit of London – of openness and acceptance – can be found.

[Images: Sonny Malhotra]

Latest

Related Reviews and Shortlists

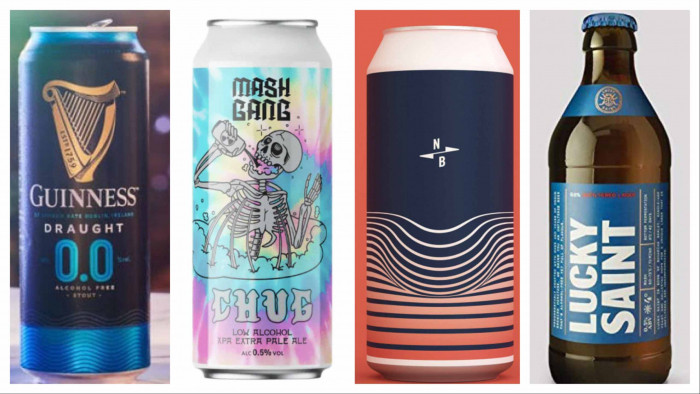

The best craft beers: 17 of the best beers