We've got 12 years to save ourselves from certain climate change death - so why won't we do anything?

A brief history of climate change and our quest to save the planet - and why there is still hope

Two years ago, I went to the excellent New Scientist Live event in London, headlined by a fantastical and captivating talk from astronaut Tim Peake, who enthralled adults and kids alike as he talked of his adventures on board the International Space Station. Meanwhile, people bustled around the event taking in various sessions on the exploration of Mars and the advances in Virtual Reality tech, as well as a mockup of the vehicle which holds the world’s land speed record, the Bloodhound SSC.

Less well-attended was a talk on the ‘Earth Stage’ by Professor Alice Larkin entitled ‘How to stop (more) climate change’. It was straightforward, uncompromising, contained no ‘magic sparkle’ and would have bored any kids watching to death.

It was also, by a distance, the most captivating and memorable hour of the entire event.

Over the course of sixty minutes, Larkin calmly and clearly explained just how screwed the entire planet was going to be from the effects of climate change. But the difference between this presentation and the frequent proclamations of doom that we’ve read over the past decade or two were the timescales discussed.

Scientists, in my experience, have always been reluctant to put precise dates on things; my general perception of global warming - no doubt, like your own - was that of something that would maybe lead to a few cities being submerged under the ocean by the turn of the century, if that. A real shame, no doubt, but far enough away that, selfishly, it wouldn’t affect me and, thinking of my descendants, far enough away that humanity would have a decent amount of time to sort out a solution in the meantime.

This was different. Dates like 2050 were mentioned as last-chance saloons and sentences like ‘action in the next decade or it will be too late’ spoken with deadly seriousness. Suddenly, talk of putting a man on Mars by 2060 seemed rather irrelevant, given that an inhabitable world might have ceased to be in existence by then. This, very much, was happening in my lifetime and this, very much, was going to affect me in a big way. It was legitimately terrifying.

Fast forward to this summer, with the seemingly endless heatwave, a world seemingly on fire like never before and, finally, the release on Monday of a landmark report by the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) which garnered headlines all across the world. It called for ‘urgent and unprecedented changes’ to achieve reductions in carbon pollution of 45% by 2030, and come down to zero by 2050, in order to limit temperature change to a 1.5C increase beyond which there would almost certainly be unthinkable consequences for the future of life on the planet.

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

Debra Roberts, a co-chair of the working group on impacts said, in no uncertain terms: “It’s a line in the sand and what it says to our species is that this is the moment and we must act now. This is the largest clarion bell from the science community and I hope it mobilises people and dents the mood of complacency.”

“At the moment we’re sort of really rearranging deckchairs on the Titanic.”

In fact, after a pause in the growth of emissions between 2014 and 2016 (note, a pause in growth - these were still the largest years of carbon emissions in the history of mankind), 2017 actually saw an increase. It’s almost certain that 2018 will see another year of growth. That’s right, at the moment when we were supposed to be drastically cutting everything to stand any chance of avoiding cataclysmic disaster and the certain obliteration of all living creatures on earth, we went in even harder.

And one of the main problems the scientific community has had relates to that sentence above.

I, a journalist, can state something like that. I can say something spectacular that might grab your attention and jolt your senses. Equally, I’ve looked at the evidence and it’s pretty clear that we are on the path to total, self-inflicted destruction if we don’t change our ways. A scientist cannot do this. A scientist must bookend their words with things like ‘probably’, ‘likely’, ‘we run the risk’, ‘strong possibility’, because they are bound by error bars, probability and the conventions of good science. It is a straightjacket which appears to have plagued the attempt to get anything done about the giant cannonball heading inexorably towards us.

But before we get to ‘why’, let’s establish ‘what’.

As can be seen by the events of this summer, we are already experiencing the effects of the climate warming by 1C since pre-industrial times: this much is agreed by virtually all climate scientists.

A rise in average temperature of 1.5C is currently the best we can realistically hope for. That means an increase in extreme temperatures and extreme weather events regardless of what we do. Sorry to be the bearer of bad news guys.

Beyond 1.5C - the Paris agreement, which currently is not being met, works toward 2C - we are into the realms of feedback loops and tipping points: for example the loss of permafrost by higher temperatures itself releasing trapped methane, which in turn leads to higher temperatures, which in turn leads to more ice melt.

At the current level of commitments across the world, we are not even on course for that: we are heading for 3C.

What would 3C look like? Great swathes of the world would be swallowed up by rising sea level, and extreme weather events would be of a severity that we cannot imagine. There would be mass migration, famine, wars: make no bones about it, truly apocalyptic stuff.

As one writer put it: “Based on [the UN’s climate change panel’s] description, the difference between 1.5C and 2C is basically the difference between the Hunger Games and Mad Max.

Clearly, we do not want this to happen. So what can we do? Is it too late?

Fortunately, no.

As the report spelled out, we can still limit warming to 1.5C, but we need to act now. It bears repeating: we need to cut emissions by 45% by 2030 and they need to drop to zero by 2050.

And the good news? The science and technology already exists to achieve this.

The Exponential Climate Change Roadmap was recently unveiled at the Global Climate Action Summit in San Francisco. It’s a document which outlines the global economic transformation required by 2030 to meet the Paris Agreement on climate and, importantly, breaks down all the ways - from individual, to company, to industry, to region, to country by which a 50% reduction in emissions can be achieved, all using technology and lifestyle methods which already exist.

In particular, the document stresses the potentially exponential nature of much of that technology and method; that is, that once a tipping point is reached in terms of adoption, the positive effects can grow extremely quickly, as with Moore’s Law of computing. They cite the advances in the development of solar and wind power over the last decade which is now poised to take over from fossil fuels in terms of economic efficiency, never mind their environmental benefits.

Owen Gaffney, co-lead author of the report says: “The thing with exponentials is that the speed and scale of change always surprises people. With wind and solar, they are doubling every four years and we can see that we are right at the point of the curve where the explosion happens. The fossil fuel industry should be terrified. I would be if I was them.”

Meanwhile, Duncan Geere, editor of the report, told me:

“Putting this report together made me genuinely optimistic that the kind of global changes necessary to keep warming below 1.5C are possible. I’ve been studying and writing about climate change for more than 15 years, and it’s often incredibly depressing, but working on this project made me realise that the solutions we need… already exist and just need to be scaled up.”

Reading the Roadmap is an incredibly positive experience. It details a clear and achievable way for emissions to be reduced and makes it clear that individuals are every bit as important as national governments and politicians. It lists many case studies including energy-efficient buildings, companies, modes of transport, changes in lifestyle (for example, China has set a target of halving meat consumption, a huge contributor to emissions, by 2030) and stories of cities and countries tackling their emissions head-on.

Indeed, I spoke to Professor Larkin, who explained how even apparently small energy use changes can make much bigger differences than what you might think. What is often overlooked is that when you save a unit of energy, you are not just saving that energy that you can see - say, switching off a lightbulb that’s not needed - you’re saving the energy needed to transmit the electricity to you, and you’re saving on all the wastage that comes from generating that electricity: you are saving energy all the way up the chain. In fact, it takes thirteen times as much energy as you eventually use on that activity simply to get that energy there.

She explained to me:

“People don’t realise how inefficient, in some ways, the power stations are - we’re losing 60 to 70% of the coal or the gas in just converting it into electricity - people look really surprised [when I tell them this]. You’re losing more than half of that fossil fuel when you convert it, which doesn’t happen when you’ve got renewables.”

It can be done. Crisis can be averted.

But will it?

To answer that question, it’s worth quoting Jim Skea, a co-chair of the working group on mitigation on the IPCC:

“We show it can be done within laws of physics and chemistry. Then the final tick box is political will. We cannot answer that. Only our audience can – and that is the governments that receive it.”

The audience, and governments. And, thus far, they have, in the main, shown a stunning refusal to do anything whatsoever about the catastrophe on the way.

If you have a spare half an hour, it’s worth reading this tremendous article by Nathaniel Rich of the New York Times which addresses a ten year period between 1979 and 1989 where scientists began to grasp the sheer scale of the issue of global warming - and politicians, initially, listened, coming within “several signatures of endorsing a binding, global framework to reduce carbon emissions. During those years, the conditions for success could not have been more favourable.”

In the days before climate change denial became endemic in the Republican Party, the issue of the threat of climate change was judged, in the US, by both sides, to be “a rare political winner: nonpartisan and of the highest possible stakes”.

So what went wrong?

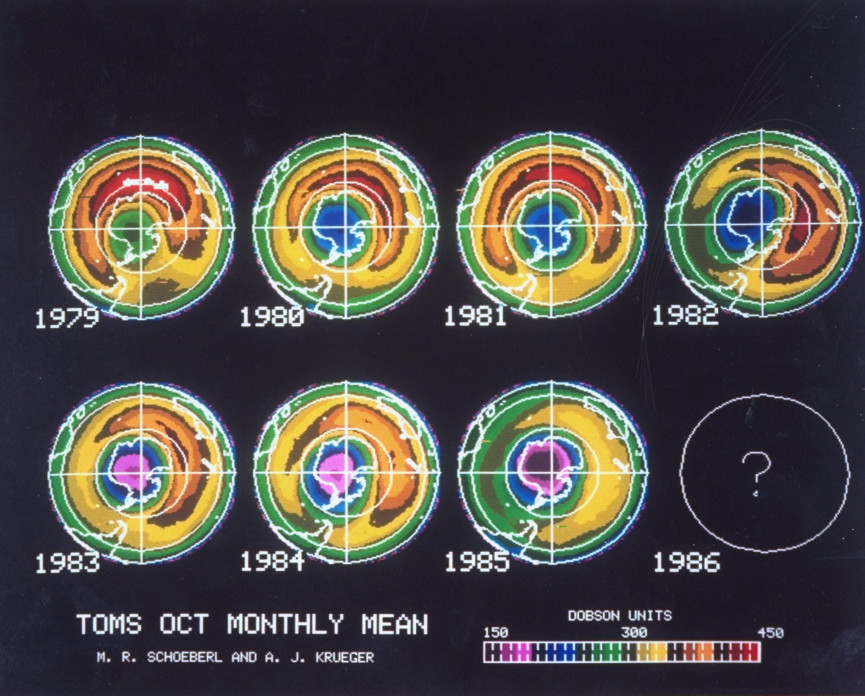

In 1986, it could not have looked rosier for action to be taken. Scientists had hit on the idea of presenting the thinning of the ozone layer over Antarctica - which had been known about for several years - as a video, demonstrating a hole; that is, reducing the science to a single, visual, recognisable thing: a hole in the ozone layer which needed fixing.

“They’re scared that some dramatic policy changes are going to be needed, and they don’t want to face up to it.”

Rich writes: “The ozone hole… had moved the public because, though it was no more visible than global warming, people could be made to see it. They could watch it grow on video. Its metaphors were emotionally wrought: Instead of summoning a glass building that sheltered plants from chilly weather… the hole evoked a violent rending of the firmament, inviting deathly radiation. Americans felt that their lives were in danger. An abstract, atmospheric problem had been reduced to the size of the human imagination. It had been made just small enough, and just large enough, to break through.”

And it worked. Public interest and pressure was huge, and the Montreal Protocol, finalised in 1987, which phased out the use of substances harmful to the ozone layer, such as CFCs, was agreed only a year later. Kofi Annan was quoted in 2017 as saying it was, “perhaps the single most successful international agreement to date”.

It was hoped - and assumed - that this would be the start of similarly successful collective action on carbon emissions. However, the incoming George HW Bush administration in 1989 sought to row back commitments, and began to squirm.

Democrat, and climate activist, Al Gore summarised it succinctly, saying: “I think they’re scared of the truth. They’re scared that… the other scientists are right and that some dramatic policy changes are going to be needed, and they don’t want to face up to it.”

The big hope: the Noordwijk summit in November 1989, which was due to see agreement of the freezing of greenhouse gas emissions at 1990 levels by 2000, with a further commitment to reduce them by 20% by 2005, was a disaster. US senator Timothy Wirth said that the outcome was evidence that the US was “not a leader but a delinquent partner.”

Rich makes the sobering observation that “More carbon has been released into the atmosphere since the final day of the Noordwijk conference… than in the entire history of civilization preceding it.”

Why did the summit fail? And why has nothing happened since?

Firstly, the actions of the fossil fuel lobby, who had begun to realise what could be achieved by spending millions of dollars on confusing the debate, confusing the public, suppressing scientific announcements and simply bribing politicians to vote in their interest. As a result, environmental damage, including emissions, have simply not been factored in to the economy. There is no cost for throwing thousands of tons of CO2 into the air. Large users of carbon resources in electricity generation, such as the United States, Russia, and China, have continually resisted the morally sensible, and eminently workable system of carbon taxation.

Secondly, the weakness of politicians, who seem bound by the timescales of elections, unable and unwilling to make unpopular short-term decisions for the long-term good. As John Sununu, a member of the Bush administration, who Rich heavily implicates in the failure of the US at Noordwijk, puts it: “The leaders in the world at that time [in 1989] were at a stage where they were all looking how to seem like they were supporting the policy without having to make hard commitments that would cost their nations serious resources. Frankly, that’s about where we are today.”

Larkin says: “I think what I find most frustrating, whatever the political situation, is decision makers not feeling empowered, or not being brave enough to take difficult decisions for the benefit of the climate. Difficult decisions are taken in many areas, but it still feels like it’s not top of the priority list and it still gets superseded by short-term economic decisions rather than long-term prosperity, sustainability-type decisions… I think as long as we prioritise those economic decisions - I don’t mean never taking heed of some economic arguments - but climate change is always second to these bigger decisions about economic growth.”

Thirdly, the weakness of our political framework: a system set up on such short cycles is inherently more unlikely to concern itself with long-term plans. This has been shown in the fact that China, one of the world’s biggest emitters, is now leading the way on some green initiatives; this includes some unpopular measures, but important long-term decisions are made somewhat easier to make when one doesn’t have to concern oneself with things like democracy, and public opinions.

But fourthly: normal citizens in the West. Regardless of the system, why have we consistently elected governments who have not made climate change a priority? The people of the United States (admittedly, not the majority) have just elected a president who does not - or rather will not - believe in climate change. Why was he elected? In part because he promised to return jobs to coal mining areas. Can there possibly be a more short-term decision made in the history of mankind by people than this? The people of the UK have voted for a Brexit, a decision that will almost certainly lead to a lowering of environmental standards in the race to the bottom to secure trade deals upon leaving the EU. Prior to this, they voted in a government who promised to “cut the green crap”. A government is currently in power that backed a fracking ‘revolution’.

Time and time again, people have decided at the ballot box to prioritise their own short-term standard of living over the ability of future generations to even exist. Taking those pointless long haul flights instead of using a virtual conference because they fancy a business jolly, even though it will literally kill people in the future.

One can argue that the Trump voters of places like West Virginia were simply displaying animal instincts: if you’re jobless and fighting for survival, who can blame you for grabbing on to something which might be bad in the long term but makes sure you can pay the rent and your family eats for the next couple of years?

It’s a mixture of two things. One, an inherent flaw in democracy - if any politican dares to come along and suggest that your standard of living might go down in the short term to meet a long-term need - “sorry guys, no more meat or aviation”, then someone will always come along and say “vote for me, it will be fine”, and they’re likely to win.

But, secondly, it’s also base human selfishness. And there’s a certain sense that people in the West have the knowledge, deep down, that they, the world’s richest people, will be the ones who will be able to best attempt adapt to any new hellscape of a future Earth.

As Larkin says: “A big temperature change like that over time, if you’re in a country that has got a lot of infrastructure, and people have lots of money, and they can put air conditioning in, then there are ways in which certain parts of society will adapt, to some extent, to this and will be able to adapt over time. But as is always the case it’s the most vulnerable, the poorest of the world, who are already feeling the effects of climate changes, who don’t have the money for shoring up the infrastructure and building in resilience and so on.”

Of course, an oft-cited reason is people’s belief that a new technology will come along and fix all of our problems in one fell swoop, negating the need for us to change any elements of our lifestyles.

As always, however, there’s a but. Professor Larkin explains:

“Thinking that there will be some technology that will come along in 2050 and sorts all this out, I think that’s where it feels really misguided, and really irresponsible because it’s sort of saying ‘oh well we won’t worry about future generations because something’s going to come along and that’ll sort you out”. This is in our lifetimes, so we will see the damage that we’re doing. There might be something that we haven’t thought of that’s going to help, but it’s unlikely that one technology will come along and sort it all out - and even if you think of something that’s going to make a big difference, the likelihood of it being rolled out across the world in the way in which it can make a massive impact on a global scale, the scale is just far too big.

“There’s a lot of interest at the moment on these negative emission technologies - things that suck CO2 out of the atmosphere… but we’re so far off solving the problem that we really need to look at the things we’ve already got and how we’re actually using energy and what people are doing with that energy and how are we developing and building new towns and cities and what can we do to retrofit the ones that we’ve already got with the stuff that we know about.

“The problem is it’s a lot more boring not to think about a brand new technology and people like to think there’s some exciting whizzy thing out there that’s just gonna sort it out and that’s much more interesting than thinking well did I really need to drive that three miles or could I have just got the bus that goes from my door?”

“Think about mobile phones, they started in the 1980s… mobile phone technology has been around for a really long time, now it’s commonplace and we’re all using it but that takes several decades - and there’s lots of studies on innovation to show that for something to actually be rolled out in a way that is pervasive in society and everybody is using and is making a big difference, it takes decades. It’s great to hear about cool new technology - but we haven’t got decades.”

Of course, paradoxically, Brexit was proof that some people are willing to vote to make an economic sacrifice to achieve a different goal - the ‘we know what we voted for’ brigade, so it’s possible that the same thing could happen with a party that committed to tackling climate change, if it were possible to generate the same depth of feeling on it as something like immigration.

Brexit itself, though unlikely, could even enable this, with Larkin suggesting: “If we are to leave the EU, then one of the things we could do is have a much stricter target on the grams of CO2 per km across car fleets for example, that’s the kind of thing that’s done better at an EU scale, but we could have been much stricter and engineers would have responded to it - the car manufacturers, they would have grumbled, but then they’d have responded.

“Could we do some of these [initiatives like the successful plastic bag tax] on the energy side, that will actually really start to drive us in a different direction? Perhaps, because, at the moment we’re sort of really rearranging deckchairs on the Titanic.”

“I think we underestimate sometimes how much influence and power we might have over other people”

Maybe it is unfair to say that people are selfish, and that they don’t care. Perhaps, until now, people have simply not been educated enough on what exactly is going to happen. Is it the fault of climate change deniers that they are that poorly educated in science? People care about their families, they care about their grandchildren, they care about inheritance, so why do they seemingly not care that they are potentially going to live in a ruined world?

Perhaps they have simply not understood the message, and the severity of it: they didn’t feel the fear and the danger that they needed to be motivated.

Perhaps, as humans, we simply cannot deal philosophically with something we cannot tangibly feel and which is so existentially huge. Much better to concentrate on small tasks just to get through the day.

Indeed: my confession. I did not speak to Professor Larkin this week, after the release of the report, I spoke to her two years ago. I pushed it aside, it fell down the digital cracks, something else came up which took my attention away and then I never went back to it.

It’s what we all do every single day, push it to one side because it’s simply too much to deal with.

Virtually everything she had said two years ago was still correct, and was backed up by the new report. And in those two years, during which, I’m sure she was merely one of many similar voices in the scientific community saying the same things, no one in the outside world had listened. No one had done anything.

But perhaps this summer of wildfires and heatwaves and this uncompromising missive from the IPCC will be the turning point. It’s here, it’s in our faces and it’s finally undeniable. And, as the Roadmap shows, it is possible and the tools are there to do something about it.

And both Larkin and Geere agree that change can come from the individual.

“I don’t think it’s just up to politicians, I think it’s also up to us,” says Larkin.

“If you’re a schoolteacher and you talk to kids, try and find out, discuss what you can do over that kind of scale… in the office - I think we underestimate sometimes how much influence and power we might have over other people or even just getting the conversation going.”

Geere explains: “There are three big things that everyone can do to make a difference. Firstly, make climate change a factor in the decisions you make around what you eat, how you travel, and what you buy. Secondly, talk about climate change with your friends, family and colleagues. Finally, demand that politicians and companies make it easier and cheaper to do the right thing for the climate.”

But we cannot be complacent - the fossil fuel lobbying has not stopped. Just a day after the IPCC announcement, the boss of Shell, Ben Van Buerden, was saying that Shell’s core business, “is, and will be for the foreseeable future, very much in oil and gas,” while Saad al-Kaabi, chief executive of Qatar Petroleum, said, “We believe natural gas will continue to play a key role, not as a so-called transition fuel but rather in our view, a destination fuel.” They’re not listening. They don’t get it. Because they don’t care.

In addition, is the UK government, for example, going to even be able to do anything in the next 12 years, given the current - and likely ongoing gridlock over Brexit?

Two years ago, Larkin was sceptical.

“I just don’t think the difficult decisions will be taken by our politicians if they don’t think we’re on board with it… The 2 degree target, it’s a massive ask. And at the moment, I don’t see the kind of concerted effort that from our kind of analysis shows is necessary, I don’t see that happening at the moment. In the next couple of years, if people really start to look at what Paris goals really mean, maybe we might see some change, but it needs to be massively accelerated, basically. I probably would say you had less [than 10 years] even, to be honest. We really need to have shown that we’ve made a big difference in ten years already - emissions need to have stopped growing and come down globally, which is a massive ask. We need to take Paris, look at what it says, and actually deliver it in a meaningful way.

“We need to put more effort in, now.”

And that message goes for everyone: individuals, companies, sectors, regions and nations. Otherwise, it’s very simple: we all die.

Has that got your attention now?

Get our best stories, delivered daily for free

Get exclusive shortlists, celebrity interviews and the best deals on the products you care about, straight to your inbox.

(Images: Getty)