Big films on the small screen: How Netflix is becoming more cinematic

From 'Bright' to 'The Cloverfield Paradox', Netflix is moving into blockbusters

I once tried to watch Titanic on a smartphone, which is obviously a disgraceful thing to do. Everything about that film, from the behemoth ship itself to Kate Winslet’s sweaty hand sliding down a sensationally steamed-up window, was clearly intended for the big screen. Watching the ‘unsinkable’ vessel tear in half and plunge into the black, icy sea just doesn’t have the same impact if you have to squint to see it and have the option of pausing to get some biscuits.

The obvious benefit of watching such a film in the cinema is total immersion. And having your skin turned inside out by atom-altering surround sound. That feeling, as well as being able to share it with an audience, is exactly why so many directors make their films with the big screen in mind, and why theatrical releases are the traditional route for production companies. But thanks to Netflix, that may all be about to change.

In 2017, David Ayer’s buddy cop fantasy film Bright became the most expensive Netflix movie ever, being picked up by the company for $90 million. Will Smith starred as a cool human, and Joel Edgerton played an orc with ink blotches on his head. It wasn’t well received critically, but was watched by more than 11 million people in its first three days. More important than critical acclaim or ratings, however, the film was a statement of intent; a statement that the streaming service was ready to increase the scale of its movies to near cinematic level, and bring it to people’s TVs and portable devices.

And the ante has decisively been upped in 2018, with Netflix acquiring even more big screen-worthy titles, such as The Cloverfield Paradox, Annihilation and Mute.

Will Smith stars in Bright, the most expensive movie Netflix have ever made

The Cloverfield Paradox, under the stewardship of J.J. Abrams, was not only handed to the streaming platform, but was also released without any notice or prior promotional material. Which, being an unprecedented thing in film marketing, temporarily melted everyone’s minds.

“The series had always been so much about surprise,” said Abrams in a Netflix Q&A screening – ironically held in a cinema. The shock announcement of the film’s sudden upload played on the franchise’s fondness for surprising its audience, but what was then even more surprising was the scale of the film itself – nothing about it feels small, from its grandiose, dimension-tampering premise, to its impossibly expensive-looking space station that zaps Earth with a benign Death Star laser. Yet this would all be witnessed on the small screen.

Alex Garland’s Annihilation has a more complicated story behind its distribution. Head of Skydance Productions, David Ellison, was concerned that the sci-fi movie starring Natalie Portman was becoming ‘too intellectual’ and ‘too complicated’ for general audiences, so a deal was made with Netflix to handle its international release, which I suppose is basically saying foreign audiences (including the UK) are extremely clever.

Paramount did get to handle its theatrical release in the US, Canada and China, but Garland made it perfectly clear that Annihilation was meant to be consumed by all audiences on the big screen.

“We made the film for cinema,” Garland told Collider. “I’ve got no problem with the small screen at all. I think there’s incredible potential within that context, but if you’re doing that, you make it for that [medium] and you think of it in those terms.”

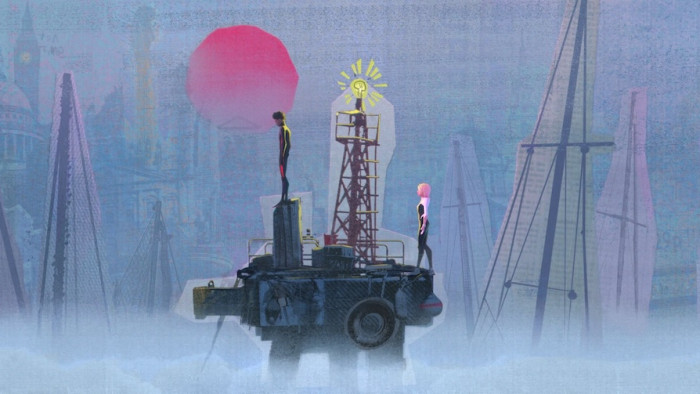

Netflix gave The Cloverfield Paradox a surprise drop in February

What’s clear is that Netflix are the ones who come out of this looking like absolute gods. They get to add a literal, cinema-quality sci-fi epic to their ever-increasing library, further highlighting their ambition to bring the big screen to your living room, bedroom and toilet seat.

Garland did point out that there are also positives for directors in this kind of situation. “One of the big plusses of Netflix is that it goes out to a lot of people and you don’t have that strange opening weekend thing where you’re wondering if anyone is going to turn up and then if they don’t, it vanishes from cinema screens in two weeks.”

Those thoughts are echoed by director Duncan Jones, whose new Blade Runner-esque film Mute is actually a Netflix Original, receiving only a handful of theatrical releases in selected cinemas. Speaking to CinemaBlend, Jones expressed his semi relief at not having to worry about opening weekend numbers, as well as the added bonus of being able to maintain a film’s secrets until release. But most importantly, he reveals how, without Netflix, he wouldn’t have had the freedom to make the version of Mute he wanted.

“Fundamentally, there would be a lot of changes,” he says. “There would be a lot of pressure to change what Mute is in order to make it more obviously accessible.” If more filmmakers start to think that only Netflix can provide them with the appropriate platform to create, then we can probably expect to see more big screen content being stuffed into our small ones.

But what’s different about Mute compared to The Cloverfield Paradox and Annihilation is that it’s a massive production that’s actually intended for Netflix, as opposed to being pawned off at the last minute or won in a game of Texas Hold ‘Em. That is surely the most significant indication of the streaming site’s ambition; that they’re not just prepared to pick up properties, but also increase the level of their own to match cinematic standards.

And if we needed a reason to really start taking Netflix seriously as a distributor of large-scale, quality films, the streaming site has now broken Academy Awards history by receiving eight Oscar nominations. That’s something it should slip into the conversation whenever one of the fancy studios questions its credentials.

Mute has not been well received by critics

With Dee Rees’s period drama Mudbound picking up four of those nominations – the same amount as Call Me By Your Name and Get Out – it suggests that the streaming platform’s model is starting to gain the approval of the industry.

But where does this leave cinema if more production companies decide to go straight to streaming? Will it eventually become a forgotten pastime, like playing Poohsticks? Well, if the comments of the aforementioned directors are anything to go by, big screen fans shouldn’t be too worried, as filmmakers by and large still regard a theatrical release as the absolute pinnacle.

Christopher Nolan is a prime example of someone who believes that, and to prove it, he made the intense, war-survival epic Dunkirk, a film that takes ‘big screen’ as literally as possible, and isn’t satisfied until it melts your face.

Nolan himself has said that he would rather Netflix adopted Amazon’s model and allowed its great films to be released in cinemas before being streamed. That’s a solution that could not only see the company muscle its way into the big screen game, but also make them an even more appealing prospect to filmmakers passionate about the cinematic experience.

But for now, Netflix is acquiring and creating genuine cinematic content that seems hard to believe it can even fit into a small screen. As a viable option for those looking for more creative freedom, it’s not a trend that’s likely to slow down, either. And as far as audiences are concerned – let’s face it – some people would rather just press play and enjoy the spectacle of a big screen film while chewing on pizza crusts.

(Images: Netflix)