I killed a crab and I liked it

How can you face up to the real truths behind eating meat? By killing your dinner with your bare hands

We’ve all seen videos of pigs being mistreated in abattoirs, and tried to forget stories of chicks being ground up in giant blenders. More recently, whistle-blowers have ‘exposed’ the realities of dairy farming – how baby cows are routinely stolen from their artificially-inseminated mothers, who are then strapped to barbaric milking machines until they pus and bleed.

We’re more clued up, yet more confused about food than ever. I don’t know about you, but I condemn these realities – while taking milk in my tea, and craving KFC on a hangover.

So how can we stop passively scrolling and make informed decisions about what to eat? Do something visceral, I thought. Force myself to actually *do* something. I would murder an animal – a crab – with my bare hands, then eat it.

“That’s disgusting, I could never do that”, many (meat-eating) friends told me. “Start with a cow or a pig”, others advised – “crabs don’t even count”. Edging away from the “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others” argument (I’m *sure* I’ve heard that somewhere before) I contacted Bompas and Parr.

‘Architectural foodsmiths' Sam Bompas and Harry Parr promised a dining experience that would give a short lesson in provenance, before guiding the killing and de-shelling of an ethically sourced Dorset crab. For £45, Londoners could ’Kill It, Eat It’ amid the cruise ship glamour of the Mondrian hotel.

Mark Zuckerberg pledged to only eat meat he’d killed himself for an entire year in 2011, so I felt I was in good company. Becoming “personally involved” in the process, he couldn’t ignore the grim reality of animal slaughter – would I end up feeling the same?

As an intense animal lover, I had mixed feelings, the hypocrisy of a meat eater feeling physically sick for weeks leading up to the kill not lost on me. Some days I agonised over ending the life of another creature, on others I worried about the fact I wasn’t worried, at all. All this to be expected, in a world where M&S adverts whisper to us from across the living room, Nigella Lawson pants as she cracks the breastbones of spatchcock chickens and Jason Biggs fucks pies. Our relationship with food is complicated, evocative and divisive.

“Now, take your mallets and decorate them with these stick-on gems. If you’re going to kill your own dinner, you should do it in style”, I was told as I pulled on a highlighter-pink tabard and prepared to murder my first living creature with a big metal spike.

“Like a vajazzle? You want me to vajazzle this mallet?” I asked, hating myself intensely.

“Ooh!” squealed a fellow killer enthusiastically. “This is all very Bowie, isn’t it?!”

Leading up to this day, I’d focused purely on getting it over with (and how to swerve PETA @ing me, tbh). Expecting a funeral-like send off for the little darlings, I felt chagrin when anyone dared to have fun. Is it wrong to enjoy the act, if done so humanely? If an animal doesn’t want to die, does a humane kill exist at all? Is it a sport if both sides don’t know they’re in the game?

I shook off these doubts as a chef explained how to locate a flap that protects a crab’s vital organs and lift it to expose soft flesh. Driving a metal stick into the crab’s heart ensures a quick kill – though the accompanying pamphlet read coldly: “You may wish to wait for your crab’s limbs to stop moving before cooking, but it’s effectively dead now”.

I reminded myself I was there to learn something and went for it. I can confirm, nothing changes your relationship with food quicker than watching the life wheeze out of something you’ve just stabbed – mouth foaming, nerve endings twitching for what seems like eternity – before you smash open its protective shell with a sparkly red hammer.

Plied with champagne while chefs whisked away the evidence, I found myself blocking out what I’d just done – but when it came to chowing down, I didn’t have too much trouble. I can see how a year’s worth of abstention and killing experiences might lead to reverence like Zuckerberg’s, but not being an internet billionaire myself, this lifestyle change would be pretty tricky.

It’s estimated that there are around 3 million vegetarians in Britain – and in May 2016 more than 1% of the population were vegan. This could be due to its purported health benefits (lower cholesterol, reduced risk of death from heart disease and cancer, to name a few) but I’ll bet the slew of graphic farming and slaughterhouse videos that keep dripping into our timelines has something to do with it. Faced with the task of killing and cooking our own meals every day, I’m sure the numbers would go up, and that I’d be one of them.

Zuckerberg said: “I’ve learned a lot about sustainable farming and raising of animals… the most interesting thing was how special it felt to eat it after having not eaten any seafood or meat in a while”. For me, it broke the barrier between clinical, packaged meats and where they come from – but served as more of a kick start for educating myself about food. My realistic takeaway was to limit meat and dairy, savour the experience when I do eat it, and try harder to educate myself on the subject.

For every picture of Salt Bae practically lubing up a Tomahawk steak, there’s a documentary listing the horrors of carnivorism (Simon Amstell’s Carnage is particularly jarring). There’s now so much information available to us that there’s really no excuse not to take it. What you do with that information, though, is up to you.

Latest

Related Reviews and Shortlists

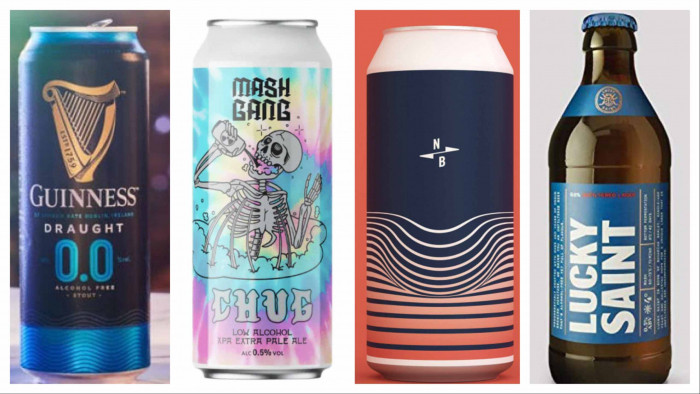

The best craft beers: 17 of the best beers