Jo Nesbø is the hottest property in Hollywood: Emily Phillips meets Nordic Noir’s big overachiever

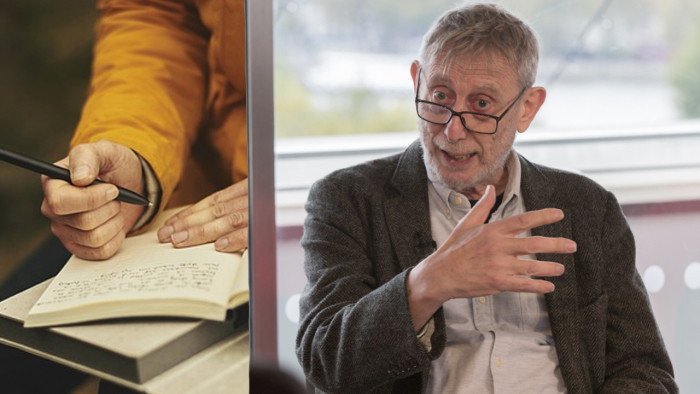

It’s 10am and Jo Nesbø has been in Oslo’s Bølgen & Moi café since the early hours. He’s jet-lagged (and tanned), after a trip to Asia, and he’s exploited the unearthly awakening to catch up on his writing under industrial light bulb chandeliers.

His new book, The Son, is his first standalone story in a while – Nesbø having made his name these past 17 years with tough and tortured detective Harry Hole. His break into novels at the ripe age of 37 moved him on from previous incarnations as a footballer, economist and frontman of Norway’s premier rock band Di Derre, propelling him to bestseller status the world over. The Son, unlike Hole outings such as Police and The Snowman, has a bigger inspiration – the Bible.

Not satisfied with taking one existential break from his comfort zone, Nesbø has also penned a children’s series about mad scientist Doctor Proctor, and later this year will also launch a new set of thrillers – this time written under the pseudonym Tom Johansen. One of the stories has already been optioned for a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio.

So does this man ever sleep? And why is it these Nordic types have a seemingly bottomless hub of creative energy? We asked Jo Nesbø whether there’s something in the water (so we can have a glass ourselves).

What’s the process of going from professional footballer, to banker, to rock star and bestselling author?

For the people who know me, writing crime stories was going back to my roots. I would write long essays at school, with a title like 'Nice Day In The Woods’ and [then] nobody would come back alive. Then I released my first album – I hadn’t learned the guitar until I was 22 – and I would be the guy who wrote the lyrics for my friends’ bands. So they were really surprised when I said at 32, “I’m in a band now.” When I wrote my first novel, I told my friends and they were like, “Yeah, of course, what took you so long?”

And you became a football player straight out of school?

When I was young, I played for Molde, who are one of the best teams in Norway. I was one of the key [youth] players so I was picked for the senior team. Then I tore the ligaments in both knees when I was 19 and it was game over. At the time, my goal was to play professionally for Tottenham, which for me seemed quite realistic.

Following that, you worked as a stockbroker. Did having a normal career aid your writing?

I started working as a stockbroker when I was 26. By that time, I’d worked as a taxi driver, in a factory, at a storage house, had a short stint as a seaman, and I’d also been in the air force for two years. I think it was more important that I’d had many different jobs, that I’d met people from all walks of life. I had two jobs. I worked as a stockbroker by day and was in the band. I was the only one in the band with a day job, which was strange, because I was the songwriter and singer. But I needed that normal life. There’s something sad about waking up on a Monday morning and having to wait until Friday to be a pop star again.

You’re obviously an energetic person…

No, I’m actually quite lazy, but I have organised my life in such a way, that when I have these bursts of energy, I can get out my typewriter.

What’s your day-to-day routine?

I don’t really have a routine – just whenever I have time to write, I write. So if I’m here in Oslo, I could come down here or to one of the other cafés. I work in airports, on trains, in waiting rooms. Writing is something I do when I’ve got nothing else to do. If I’m planning to write from 8 until 4, I won’t do it. If I planned it like that, like a job, you would give up the best part of being a writer, which is waking up in the morning and thinking “What do I feel like today?” Most of the time, I feel like writing.

What do you think of the British obsession with Scandinavian culture manifested in things like the Nordicana festival? Do you understand it?

No, I don’t. I understand that right now, there are some good TV series makers, there are some good crime writers, but then again, there are just as many bad movies, and bad crime novels in Scandinavia as everywhere else.

How long did it take to come up with Harry Hole?

It took 33 hours. I was going to Australia and I wanted to write a crime novel while I was there. So I just brought my laptop. I planned Harry on the plane, and when I got to the hotel, I was jet-lagged so I started writing. I had five weeks in which to write a novel. I went to Sydney and stayed in a small room in the red light district and used that as my base both for writing and also for the story.

Was there anyone who became the inspiration for Hole?

I guess that writers write about themselves. You just can’t avoid it. When you’re writing, you have to find something in yourself which relates to the characters. Even the psychopath, you have to find your inner psychopath and enlarge that bit of yourself. With Harry, I’ve been writing about him for so many years that it’s inevitable I use myself in that character. You can use your character to express what you think and feel, or you can use them to express something that you don’t think and feel. Bad things. Politically incorrect things. It’s liberating in a way.

And one of the things you express quite strongly in your books is extreme violence…

Sometimes I do write about sadistic people, and in order to do that, I have try to seek out my inner sadist. In Police I wrote that Harry is having rape fantasies. It doesn’t mean he really wants to rape somebody. It’s like you’re playing with your reader’s sympathy for the character. I work with stories based on the human condition and the human psyche – but then I have used humans in stories that may have a moral aspect.

The way you do in The Son…

The Son is based, of course, on the bible, and the reason why I’m so fascinated with the bible is not because I’m a religious person, but because there are so many damn good stories – and they are really psychologically and morally challenging.

Aside from the biblical themes, it is still a crime novel. Do you have inside police sources?

I do research to the extent that I need it – I send them chapters to see if things are plausible. But I’m not really interested in real crime. I just use the crime genre as a vehicle for the stories I want to tell.

And how about writing under a pen name – was that freeing?

It started out as me writing a story about the kidnap of a fictional Norwegian-Danish writer named Tom Johansen, called The Kidnapping Of Tom Johansen. [This character] published a novel in the Seventies called Blood On Snow and it became a minor cult classic. I thought, ‘I want to write Blood On Snow and Blood On Snow II, and publish them under the name of Tom Johansen’. We had already written Wikipedia articles, pictures, so the plan was this big scam. But then we received advice from our lawyers that you can’t really do that without getting sued.

And it’s proved so popular that now Leonardo DiCaprio has signed on to be in the film of Blood On Snow?

I just read it in an email from my agent. What I’ve learned about movies is that you can’t take anything for granted until they phone you and say, “We’re shooting now”.

Martin Scorsese is also signed on to direct your book The Snowman. Has he got your blessing to do what he likes with it?

Yeah. I mean, I wasn’t too happy with selling the rights before the series was finished, but they said Martin Scorsese called, I considered it and the book is there. The movie is another storyteller telling his story and in one way the further away from the book they take it, the happier I’ll be. I’ll think “OK, that’s a movie”; my book was input. Hopefully helpful input, but that is it. If you want to read the book, it’s there.

The Son is out on 10 April (Harvill Secker)

(Images: PA/Rex/Momentum)