Loyle Carner on Croydon, being a softie, and cooking ragu on date night

"People say 'Loyle Carner is a softie', I don't give a shit. Loyle Carner pays the mortgage for his mum."

“People keep cussing me out about living in Croydon,” says Loyle Carner, downing a Vita Coco. It was a definite no to coffee because that’s “the devil’s drink”. We’re sat in a brilliant white room listening to old school hip-hop and a little Gregory Isaacs in a brick building overlooking Shoreditch Park, a scrap of grass just off Old Street with its deluge of buses and fancy, glass-fronted new-media businesses.

“Everyone keeps saying you need to bring your passport and that you get jet lag when you come back from Croydon. I swear it’s not even that far...”.

He pauses and picks at some mud flecks on the cuff of his black Dickies. “Yeah, I guess it is quite far. There’s not much Croydon is known for: Ikea, Stormzy, being really far away. Maybe I could do a collaboration with Ikea...”.

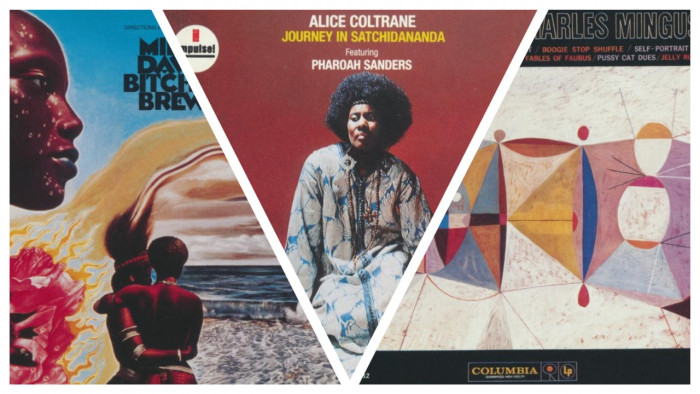

Just a few days ago, the 22-year-old rapper’s debut album Yesterday’s Gone was nominated for the Mercury Prize. It was praised for its brutal emotional honesty and stories of abandonment from his biological dad and ex-girlfriends, stories he’d grown accustomed to stewing over during long, quiet, half-pissed journeys home from nights out in the city back to deepest, darkest south London.

But while his long journey home has afforded him welcome critical distance, it’s been messing with what he describes as his ‘phenomenal’ BBQ skills. “I do a BBQ thing at the end of each year called Caribbean Christmas,” says Carner, who is half-Guyanese. “It's Caribbean Christmas dinner and everyone brings something. It’s great, but because I’m so far away, and because you can only wrap up certain stuff, everyone brings the same thing and we’re sat there with like, seven fucking mac ‘n’ cheeses and they all end up burnt and uneaten...”. He shakes his head, the pain of so much wasted food apparently haunting him.

Food’s always been a big part of his life, ever since his grandparents opened his tiny eyes to global cuisine as a kid. “My granddad was in the Navy and he’d always cook me lots of African food. But he was Scottish, so it’d be like, mince and tatties with jollof rice. I swear it was only a few years ago I realised he didn’t invent jollof. I was at a friends house and I was like ‘Rah, you’re cooking my granddad’s special ketchup-rice?’.”

As Loyle speaks he bounces around in his chair, smacking one hand with the back of the other, gesticulating animatedly, or nervously playing with the rings on his fingers when he gets introspective. He rarely stays in one place very long: one minute he’s talking tatties and jollof, the next he’s looking through his phone in search of a vintage Scottish football shirt he’s got his eye on. Diagnosed with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) at an early age, cooking is the only thing that really calms him down.

“It’s not ADD,” he says. “I’ve definitely got the Hyperactivity part in there.”

Since returning from a hectic tour schedule – “I swear I’ve spent 300 of the last 365 days on the road” – Loyle has found himself consciously using cooking as a tool for mindfulness, as a way to switch off while still being useful.

“It’s how I chill,” he says. “I do it when I’m not even hungry, cooking something that takes hours. I love it because it takes up all of me: with ADHD, you get distracted easily, but in cooking, it’s not a negative. You want loads happening: you’re chopping this, that thing’s on fire, this thing’s going in the grill, that’s in the pan. When I started cooking, for the first time in my life, my ADHD became a positive. It all just clicked...” He looks contemplative then excitedly smacks his left hand with his right. “And plus I got this sick steak tip off Heston––“

We cut him off with a clanggg noise at the name he just dropped. Loyle shakes his head. “He rang me when I was in Australia to say he was interested in something I’d done about ADHD and food in the Guardian Guide. He invited us over to one of his restaurants for food and a chat then absolutely destroyed me at table tennis. He’s a monster at it. But still… that was a pretty bad name-drop, innit?”

Yes, we tell him, it was quite bad. (The steak tip was just ‘don’t move the steak much’, by the way) But it’s fine: it must be weird going from nobody knowing you to being someone a lot of people know or at least sort-of recognise.

“It's always ‘sort-of recognise’, though,” says Loyle, getting himself another drink. “I always get ‘Don’t I know you from somewhere?’ Loads of people tagged me after a Tom Misch show at Somerset House I wasn’t even at, thinking I was Novelist…”.

Or they think he knows Skepta. In New York for a series of sold out shows, Carner says he was constantly being pigeonholed with North London’s king of grime.

“I swear it would happen at least two or three times a day. I'd tell them we make hip-hop and we're from London and people would be like ‘Cool! Like Skepta? Like grime? Do you know him?’ And then when you say no, they don't care anymore about anything you've got to say.” He shakes his head and shrugs: just one of those things.

“It was cool over there, but I swear you go and, to them, you’re either Skepta or you’re Hugh Grant. Tea and crumpets, all that. I swear they were expecting me to be like rap’s Colin Firth or something.”

Like you’ve read a million times, from a million other ‘fresh new acts’, Loyle is another artist annoyed by attempts to label him, which, to be fair, have been pretty lazy. “I’ve got my shit-list,” he says, grabbing for his phone, scrolling through it. “Yeah, this one: they went to my show, gave me three stars, and called me ‘the sentimental face of grime’. What is that about? That’s nonsense.” But sentimentality is certainly not the part of that description he rallies against.

“People call me a softie because I talk about certain thoughts and feelings that that other people don’t,” he says. Does he ever worry about his ‘nice bloke’ image? “I don’t think about it,” he says. “It’s just who I am. My mum calls me ‘the nice guy of rap’ to her friends. She calls me a sweetheart.”

He is a nice bloke, though. I strike off another interview cliche in my notebook, thinking it’d be good to grab a beer with him. But for all his goofy charm, he is not a rapper who shies away from getting pretty emo: alcoholism, regret, disappointment, emotional betrayal, tears, fears, and loss are all stocks in trade. Are people ever like, ‘cheer up, mate’?

“Oh, all the time. They say the usual ‘man up’ or ‘grow some balls’ stuff. And sometimes they’re like ‘I don't need you to tell me how I feel about my dad’ or ‘Why is this guy always moaning?’”.

Then there’s the other accusation that’s occasionally levelled at Loyle.. While he’s confrontational with his feelings on tracks, he has been accused of being a little guarded, even anodyne, in interviews. A guy that plays it safe, refusing to get involved in the kind of name-calling and tit-for-tat beefs that rap music has long been associated with. Is this part of Carner’s shrewd, career-minded game plan?

“I just don’t trust these journalists, man,” he says, shrugging. “I keep them away from my family and they still come and knock on my door, talk to my mum. My mum goes: ‘I met this really nice lady and she just wanted to chat’ and then they twist what she said and write whatever they want. I don’t care what people think. I’m just protective. I swear, if this keeps happening, in a year or so I’m done. None of you lot will ever see me ever again...”

As we walk to the roof for the photoshoot, talk - inevitably - moves back to food. He gives me his mum’s roast potato recipe and tells me his go-to date-night dish is ragu alla napoletana. It’s every meat imaginable, chucked in a pot with a load of sauce, cooked for three hours, and served with spaghetti. It sounds simple in a way that would certainly mean it’s actually quite hard. He loves it. They love it. Everyone loves it.

“I’ve fucked it up a few times, usually when I’m at someone else’s house and they distract me," he says, carrying the stylist’s bag of clips up the six-flights of stairs to the roof without being asked to. “I love cooking and girls always want me to cook for them but really, I still live at home, you know what I mean? I can’t just always be like: ‘Mum, get out’. I’ve done that a few times but it’s just tragic, man. It’s not worth it... Family are the most important to me, anyway. That’s why when people think they know me and say people go ‘Loyle Carner is a softie’, ‘Loyle Carner needs to man up’, I don’t really give a shit. Loyle Carner pays the mortgage for his mum. Loyle Carner is doing very, very grown-up, manly things.”

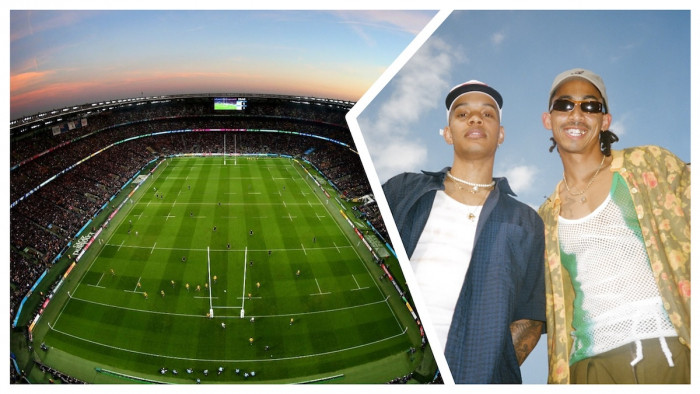

When we finally reach the roof – and really, we started to wonder if those stairs would ever end – and start shooting, the blue vista overlooking the park pocked by sandpits and kids on mountains bikes starts to feature dark clouds crowding around its edges.

“You know, when I found out about the Mercury Prize nomination, I was sat on my own at home,” says Loyle, looking out over the edge at the road beneath, a little buzz going off two cans of Red Stripe he’s just shotgunned for the camera, “and I couldn’t get through to anyone on the phone to tell them. I was just sat there with my poodle, Ringo. I think I cried a bit.”

He breaks off to do some karate moves in his new, wide-legged, non-muddy trousers before coming back to the real world. “My dad said never bet more than the price of a beer on anything… And I saw some bookies had me at 8/1 to win it,” he says, shaking another can. “Beer’s pretty expensive around here, right?”.

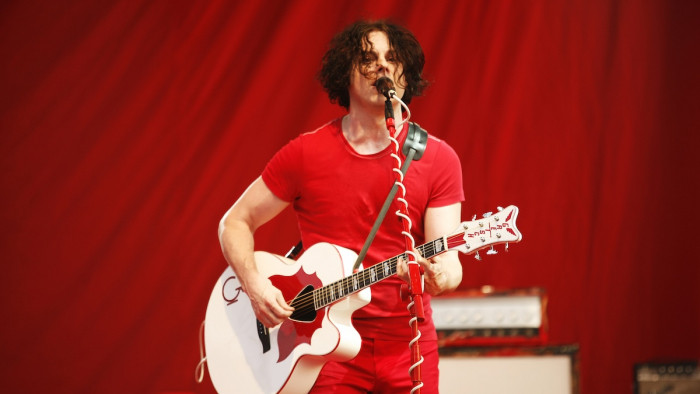

Photography by Jay Brooks. Styling by Abena Ofei. Grooming by Alexis Day.