Jamie Oliver’s solution to childhood obesity is to starve the poor

The millionaire celebrity chef has helped to ban two-for-one pizza deals in Scotland

Look, Jamie Oliver is only trying to help. If you see him snatching an ice cream out of a toddler’s hands, or grabbing a schoolboy by the ankles and confiscating his lunch money in case he spends it in Greggs, or gatecrashing every 9th birthday party in Britain to trample on the cakes, or brutally accosting delivery drivers to prevent takeaways getting to their destination, it’s because he cares. That’s why the TV chef has, successfully, lobbied Nicola Sturgeon to pledge a ban on two-for-one pizza deals in Scotland, as well as similar multi-buy promotions and price cutting on foodstuffs high in salt, fat, and sugar.

There’s a broken logic here. Oliver and Sturgeon have looked at the figures – that 14% of children in Scotland are at risk of obesity; that the risk factor for children who grow up in deprived areas is nearly double that of their more affluent counterparts; that the same risk is nearly tripled by the age of 11 – and come to a rather simple conclusion: the poorest are eating unhealthily because they cannot resist indulging in red hot deals on junk food.

In their fantasy, the poor are too stupid to realise they are being conned into diets that might increase their chances of health complications, and that they’ve been allowed too much autonomy over their meal choices. By making the shitty food these idiot poors insist on eating as expensive as healthier options, Jamie Oliver believes they will have no choice but to pick a salad over a Turkey Twizzler, unless they’re really determined to recklessly cause themselves harm financially and physically, and whose fault will it be then?

Can it be argued that this pledge will help tackle obesity in general? The answer is, of course, emphatically: no. If pizzas really are to blame, and if someone could afford to buy a sloppy Margherita regardless of price point, then they’re not going to be deterred by an end to sweet 2-for-1 bargains.

That’s bad for you, mate. (Getty Images)

See, if Jamie Oliver was serious about ridding the nation of the scourge of pizzas, he’d try to get them banned altogether, collect them all up and chuck them in a big wood fire so no one could pollute their bodies with cheese and tomato. He certainly wouldn’t open a chain of restaurants selling this doughy devil to unsuspecting punters. A cursory glance at the nutritional information for Jamie’s Italian’s £13 ‘Posh Pepperoni’ reveals that it contains more calories, saturated fat and salt, and less fibre than significantly cheaper frozen supermarketcounterparts. Certainly, it would be a bold business strategy if his aim was to start a nationwide franchise of high-street restaurants, and then set deliberately high price points to actively deter people from eating in them, and if that was his plan, then I concede: fair play, that’s commitment to a health crisis. Or maybe it’s just that, actually, Jamie Oliver has no problem foisting unhealthy pizzas on the general public, as long as they can afford the premium on them.

To be fair to Jamie Oliver, it seems harsh to criticise his commitment to alleviating inequality when he’s shown a consistent and demonstrable inability to understand basic socioeconomics. “I find it quite hard to talk about modern-day poverty,” he admits, discussing a scene in one of his shows, Ministry of Food, where a mother and child eat chips and cheese out of Styrofoam containers. “Behind them is a massive fucking TV. It just didn’t weigh up.” Here he is up front that, as a celebrity chef worth £290 million, he cannot comprehend the fact that owning a widescreen telly is hardly the preserve of the elite these days, and that if people endure enough economic hardship that they have to improvise with their crockery, they might want to afford themselves the small escapist luxury of a television instead of eating kale in front of an empty wall.

“I meet people who say, ‘You don’t understand what it’s like,’” he continues. “I just want to hug them and teleport them to the Sicilian street cleaner who has 25 mussels, 10 cherry tomatoes, and a packet of spaghetti for 60 pence, and knocks out the most amazing pasta.” One wonders what this hypothetical poor Briton would do, having been teleported to Sicily, where they do not live, and shown that: see, this street cleaner has no money like you, yet he manages not to constantly shovel rubbish into his mouth. Would they return home, inspired, and set about trying to locate where this mythical 60 pence worth of fresh produce in their local area? Or would they just feel inadequate and patronised?

Now, while hypothetical Sicilian street cleaners might have an abundance of cheap, healthy ingredients at his disposal, the reality of life in the UK is not quite the same. A study conducted by PLOS One showed a widening gulf in price between foods considered ‘healthy’ and ‘unhealthy’ by government criteria. In 2002, 1000 kcal of ‘healthy’ foods cost £5.65, while the same quantity of ‘unhealthy’ cost £1.77. By 2012, this had risen to £7.49 and £2.50 respectively – triple the cost.

Rather than attempting to raise the price of unhealthy food in line with its counterpart, it seems obvious to say we should focus on efforts to make healthier alternatives cheaper, through subsidies or else other means. When median incomes have fallen 4% while food prices have risen 11% in over the last decade, and when foodbank usage has increased 13% from 2017-2018 on the previous year (with a 6% increase in the number of children reliant on emergency food supplies), we can’t afford to accept Oliver and Sturgeon’s logic that the poorest have always been able to afford healthier options, they just choose not to. A cheap ready meal deal may not be doing someone’s health any favours, but it might be allowing them to survive. What happens when you make those options prohibitively expensive? There’s a chance that obesity will fall, but as a side effect of starvation.

It is entirely possible to maintain a well-balanced diet on a budget, of course, but it seems rarely understood that doing so isn’t as easy as simply pointing this out. For one, nutritional education is scant. If you aren’t taught how to cook healthy meals at home at a young age, or simply aren’t taught to cook altogether, then it becomes far more challenging to switch from takeaways to homemade dishes. Without an innate knowledge of cookery, it becomes even more challenging to know which ingredients have the best nutritional value and where to find them. You might be able to rustle up a spag bol, but is your recipe a necessarily healthy one? And while Jamie Oliver argues that local markets are cheaper than supermarkets, and that “if you’re going past a market, you can just grab 10 mange tout for dinner that night”, access to a local market – both in terms of distance and being able to frequent it during opening hours – is, for many, sadly not a given, particularly if you live in a ‘food desert’.

A recent YouGov survey found that one in eight Britons don’t cook from scratch, and that 46% felt this was because they just didn’t have the time. I grew up in a household where money was tight and my parents’ separate schedules were often eaten up because of this, and other pressures. They would try to cook homemade dinners for us as often as they could, but when you have a family of three kids to support (five including my half-sisters), and seemingly not enough hours in the day, then multi-buy easy dinners become a godsend, and the ability to put food on the table becomes more important than guaranteeing that it’s a meal that Nicola Sturgeon would approve of. Many others can tell similar stories of greater hardship.

If we want to make meaningful inroads towards relieving childhood obesity, then we need to look at the myriad contributing factors that lead people to being reliant on cheaper unhealthier food, rather than removing their access to it. If we can identify income inequality as a contributing factor, then we must endeavour to reduce – or else erase – it. More than pizzas, we need to confront precarious employment, depressed wages and swingeing cuts to our welfare state. We need to address the material conditions which have made our nation’s poorest poor, rather than trying to force them to lose weight by taxing them out food.

To his credit, Jamie Oliver’s intervention into school meals had a tangible benefit for children’s health, but it also increased the price of said meals during a period where the disposable income of the poorest fifth of households fell by £20 a week. One policy that everyone should get behind, then, is universal free school meals. And to Nicola Sturgeon’s credit, the SNP have done exactly that – introducing them in Scotland to all children up to the age of seven. But if we know that the risk factor for obesity increases from the ages of five to 11, then it’s a policy that should be extended, rather than weakened – as the Conservative Party have done by setting absurdly low thresholds by which children qualify. The ability to guarantee that every child in the country will receive one healthy meal every lunchtime will go a significant way to improving their diets.

But there is one final, important point. Pizza tastes really fucking good. Sometimes you don’t care whether something good for your body, you just want a pizza, because it tastes really fucking good. Sometimes you work all week in a low-paid, dead-end job and you’re tired, and you’re miserable, and you just want to gorge in a greasy artery-clogging pizza in front of your widescreen telly without Jamie Oliver wagging his finger in your face and the government pricing gouging you to quinoa. Why should it be that only the wealthy are allowed to have vices?

Latest

Related Reviews and Shortlists

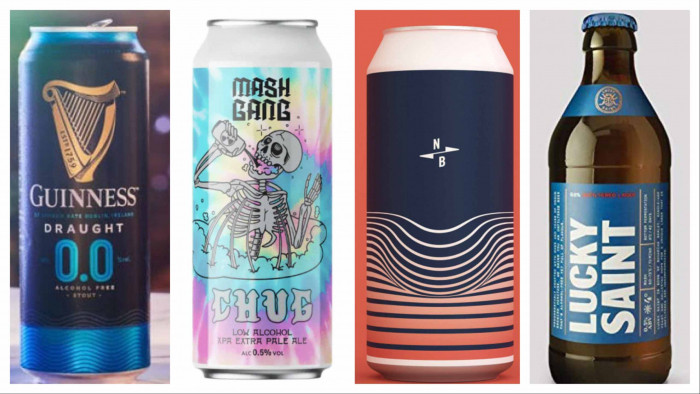

The best craft beers: 17 of the best beers