Reducetarians: the benefits of being a bad, burger-eating “vegetarian”

What to do if you hate animal cruelty but love animal flesh

Paul Franzen feels like an asshole whenever he eats dead cows.

“Cows are wonderful and adorable,” the 32-year-old game developer tells me, explaining that his love of cows – and other animals – first made him consider vegetarianism around eight months ago. “It’s very unfortunate how good they taste.”

Last month, Paul ate a “delicious” steak and cheese burrito. He isn’t a vegetarian (see: steak burrito) but he’s not exactly a meat-eater either. Monday to Friday, Paul eats no meat, instead choosing substitutes such as soy dogs and Tofurky. At restaurants, or when he visits family and friends, he eats meat.

Some people might think this makes Paul “non-vegan trash”. Last month, a vegan woman was shamed on Twitter after she bought dairy ice-cream for a crying child. The Twitter user who shamed her referred to her defenders as trash, and argued “she essentially killed one or more cows”. In 2018, standards are so high that vegans attack each other, let alone occasional meat-eaters.

At roughly 71.42 per cent vegetarian, Paul is arguably far from trash. But there is an easier way to describe his lifestyle. “Reducetarians” are people who are committed to eating less meat (and sometimes dairy and eggs) but are conscious of their own limitations. Some vegetarians and vegans – most likely ones on Twitter – argue this is selfish and wrong.

“In order to change the world, we must be realistic,” says Brian Kateman, co-founder of the Reducetarian movement and author of The Reducetarian Solution. “Meat consumption isn’t an all-or-nothing premise.

“We – the animals, the planet, and our bodies and minds – all lose when we obsess so much over perfection that we wind up giving up and doing nothing.”

Nowadays, most people do something. Meatless Mondays and Veganuary both demonstrate that humanity is more cautious about our ethical and environmental impact, but both trends are limited in timeframe. Reducetarianism – Brian argues – can have a lasting impact on our life expectancy, the planet, and animal lives.

“It’s pretty simple: the less meat we eat, the more animals we save.” If someone who eats 200lbs of meat cuts back 20 per cent – says Brian – that’s better than a person who eats 5lbs cutting back 100 per cent. According to academics at the University of Minnesota, if everyone in the world followed a Mediterranean diet (think moderate consumption of fish, dairy, and meat – but plenty of olives and veg), global greenhouse gas emissions would decline significantly. In addition, a worldwide adoption of Mediterranean, pescatarian, and vegetarian diets could reduce cancer by 10 per cent.

In 2017, sales of meat-substitute Quorn soared by sixteen per cent, while sales of beef, lamb, and pork declined by 4.2 per cent. Businesses have already seen the impact of consumers turning away from meat, sending a message to factory farmers without 100 per cent committing to the vegetarian or vegan lifestyle.

“I wanted to reframe the conversation away from ‘cheating vegans’ and ‘lazy vegetarians’ and toward positive language around meat reduction,” Brian explains.

There’s no denying that this “positive language” is, ironically, a meaty mouthful. Paul hadn’t heard the term “reducetarian” before I mentioned it, and Brian doesn’t know how many people identify as reducetarians worldwide. It’s much easier to say you simply “eat less meat” – but Brian thinks the term keeps people on track.

“People who eat less meat are more likely to go vegetarian, and people who go vegetarian are more likely to go vegan,” he says. But of course, it’s possible for things to work the other way around. I became a vegetarian a year ago before giving in so badly (and repeatedly) that I decided I was a reducetarian instead. Should I have stuck to my guns?

“Your actions matter – there’s no denying that,” Brian says when I tell him that I recently ordered £17 of KFC after a particularly depressing day. “That meal wasn’t good for your body, the planet, or animals,” (OK Brian) “but the reality is that most people in the United States eat well over 200 pounds of factory farmed meat. So if you’re doing your part by eating significantly less meat than that, give yourself a break.”

The colonel and his tempting wares

Rachel Molodetz, a 25-year-old who works in customer support, originally went pescetarian (not eating meat but eating fish) two years ago, and now makes a conscious decision to eat less meat (especially, she says, after watching Netflix’s super-pig fantasy film Okja). But if she (and Paul and I) love animals so much, why not just be vegetarians?

“I think part of the reason is just a bit of selfishness,” Rachel admits. “There are foods with meat in them that I like and don’t want to give up.” Like Paul, she eats vegetarian at home but meat at restaurants.

Brian, who became vegetarian at university but slipped up on a few Thanksgiving dinners, is now vegan. Unlike vegans who get most of the media limelight, however, Brian emphasises that mistakes aren’t the end of the world.

“I’ve probably eaten a few pieces of bread that have trace amounts of eggs in them. I sleep at hotels that undoubtedly use feathers in some of the bedding. It’s impossible to be perfect, so just let it go.” Last year, when travelling abroad he ordered minestrone soup with turned out to have meat in it. His response sums up the reducetarian way.

“I decided to eat it rather than waste it,” he says.

(Images: Anna Pelzer/Getty)

Latest

Related Reviews and Shortlists

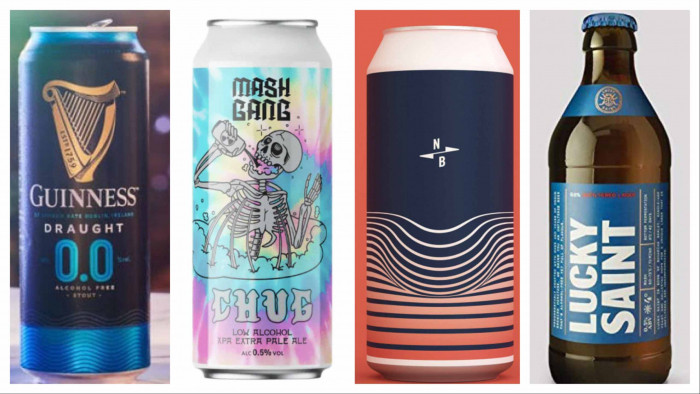

The best craft beers: 17 of the best beers