When should you give up on your favourite band?

Even if they turn rubbish, can you ever truly let them go?

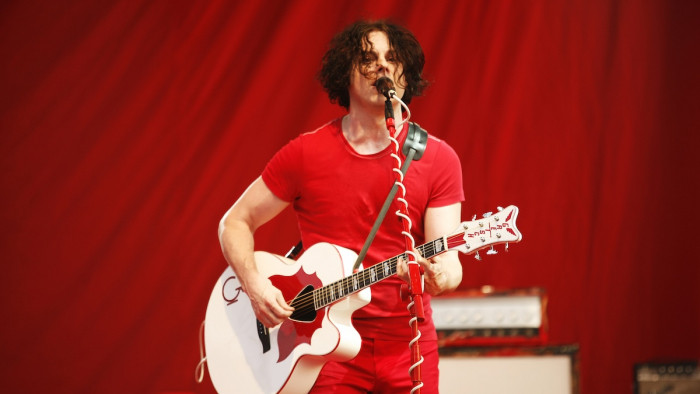

Festivals force you to make decisions. For instance: you could keep yourself relatively hygienic, or you could swerve paying £500 for a yurt and make do with a couple of baby wipes to keep the diseases at bay. You could have 15 churros in a row washed down with warmed cider and your first experience of the popular hallucinogen ‘acid’, or you could not spend a whole evening coating your tent in vomit. You could stick with your ‘friends’ and watch all the terrible bands they like, or you could split up, accept that you won’t see them again for the rest of the weekend, and see exactly who you want. A little over 10 years ago, I did just that, ambling over to Glastonbury’s Other Stage to watch Arcade Fire on my own. It remains the best festival set I’ve ever seen.

Despite basking in the particularly radiant glow of the universal critical acclaim they received following the release of their first two albums Funeral and Neon Bible, they were not yet headliners, even on the second stage, but they played as if they were closing the entire festival. Their set was comprised of 13 tracks from those two untouchably great albums, crescendoing perfectly into to a rousing five-minute long ‘(Antichrist Television Blues)’. It was a ball of sweat and fluorescent light, perfectly offset by a Somerset sunset which gradually plunged the site into darkness, as though nightfall itself was actually a calculated part of their stage show. In short, it was the kind of set that can make you fall in love with a band.

A decade on, however, and Arcade Fire have gone and done precisely the opposite with their fifth studio album Everything Now.

There have been incremental stylistic changes since their debut, and while you might point to diminishing returns in their third and fourth albums, the band’s unwavering sincerity had always remained. The main difference with Everything Now is how uninspiring and almost joyless it is. The glass-half-full fan might argue enthusiasm has been replaced with appropriate cynicism, but others, like myself, find this cynicism just falls flat.

There a high points, not many, but there are, (most notably ‘We Don’t Deserve Love’) but these almost make it worse. They demonstrate that the band haven’t lost the stylistic abilities to make the music I once I loved without hesitation, they just don’t want to. In short, it’s just bad.

I’m not alone in my feeling – the critical response has been fairly uniformly negative across the board. But critics relish each and every opportunity to tear artists down for their missteps, it’s not the same when you’re a fan, when you want it to be good. Is it possible to pan Everything Now while retaining a sincere love for the band’s earlier work, or does that same love require fans to rush to the defence of a lesser album? Does loving a band mean you have to love (or convince yourself you could love) everything they do?

While it might be unrealistic to assume one’s tastes will remain identical over a 10-year period, those bands or artists capable of making a real impact will generally do so by writing music you can never see yourself not enjoying. Even those who come into your life at a relatively young age – when your tastes are more rigidly intertwined with scene and self image – can leave a lifetime’s worth of impact. If you’re still listening over a decade later, it doesn’t matter what age you first fell in love with them.

So we come to the act of falling out of love, or of simply finding that their new releases no longer inspire those feelings of love.

It will always be difficult for an artist to have the same impact with a fifth album that they achieved with a first or second – especially in the case of Arcade Fire, whose initial appeal stemmed in part from the fact they seemed to be doing something different enough to they stand apart from the indie landfill the engulfed the lesser bands around them.

Ambivalence towards an ambitious change in direction can be written off as part diminishing returns, part diverging tastes. But it’s different when someone is trying to replicate the things they used to do so well and failing. Not expecting to be blown away to the level you were with earlier albums is one thing. Having decade-old albums still feel fresher than more recent material by the same band is quite another.

This is the point where the self-doubt begins to creep in. Is this just a blip? Will they continue being this terrible? Have they always been this terrible? Did you ever really like their music? Should you identify as a fan? Should you keep schtum when people bring them up? Maybe you should actively make fun of them? Are they, when it comes down to it, just… shit?

No. You cling on, defiantly. Eventually though, it feels like you’re playing a waiting game. The standard live set leaves you cold where it once wowed. You keep buying tickets to see them, but your expectations for the live experience have been tempered, and eventually there will be a tipping point where the bad outweighs the good. A new tour is announced. You unsubscribe from their email alerts. At this point, you have to wonder: if you’re turning your back on the band’s future, are you abandoning their past in kind? If buying their merchandise and setting reminders for their tours was something which characterised your early love for them, when that disappears there’s an argument you are going from being ‘a fan’ to ‘someone who just likes some of their albums’.

The tougher yet ultimately more rewarding option is impose a personal cut-off point unique to your relationship with the band; to enjoy what you have always loved, and know that – while it hurts – an artist is simply no longer making music for you anymore. Why expect their new direction to cater to your own specific taste? A band changing what they are doesn’t change what they were, back when you first fell in love with them. It’s possible to stop caring about new releases without losing any of the enthusiasm for your favourite albums. Their new sound won’t infect those records by osmosis, as long as you don’t let it, as long as you don’t hear the Arcade Fire of 2017 when you listen to the Arcade Fire of 2004.

An ability for a band to sustain itself as one of your ‘favourites’ is always more than just an overnight thing. They force their way into your life and consistently enough to remain there. They are what you reach to as a reliable constant, an aspect of your identity you know to be true, that helps define you – About me: I like West Ham, The Simpsons and Arcade Fire. All of these things have disappointed me in kind, and in time, but I can’t let go. Not completely.

Sometimes the easiest way to maintain your love for a band is to apply your own limits to that love. Someone will enjoy future incarnations, while they’ll probably hate the bits you loved, and that’s absolutely fine. Unless they love this new Arcade Fire album. It’s fucking shit.